A pointer to some rural and coastal gems and the scribbling they inspired

Lancashire is one of England’s best kept secrets when it comes to tourist treats. Sure – everyone’s heard of Blackpool – but that is the county’s least typical town, and it stands in intense contrast to the magical rural hideaways that make up the majority of this corner of north west England. Ours is a county steeped in history – ancient, feudal, industrial and social. There’s the mysterious to be found here too. It is a county that gently keeps its counsel, but investigate more closely and you will be rewarded with unexpected delights. In addition, there is something here not quite at peace with itself. I’ve always felt that my home county wants more of its stories to be told.

Lancashire is easily overlooked – or passed through. You may be unlucky enough to hit a closure of the M6 or find the West Coast Main Line temporarily terminated in my home town of Preston, but otherwise the eager holiday maker en route northwards to the Lake District or Scotland, or dashing south to Wales, the midlands and beyond, will probably pay scant attention to Lancashire’s sweeping coastal plains, fast-flowing river valleys and magnificent upland moors. If, on the other hand, you take time to deliberately stop, stare and imbibe the air, take care; because the secret spells of this land may creep into the creative corners of your cranium and show you the invisible. Perhaps you, like me, will be prompted to share your impressions.

Talking of secrets…

Fulk took him to the top of the great keep. The day was cloudy but clear and a strong westerly wind tugged their hair and sharpened their faces as they peered into it.

“Is that the sea?” said Will.

“Well, it’s the coast,” said Fulk.

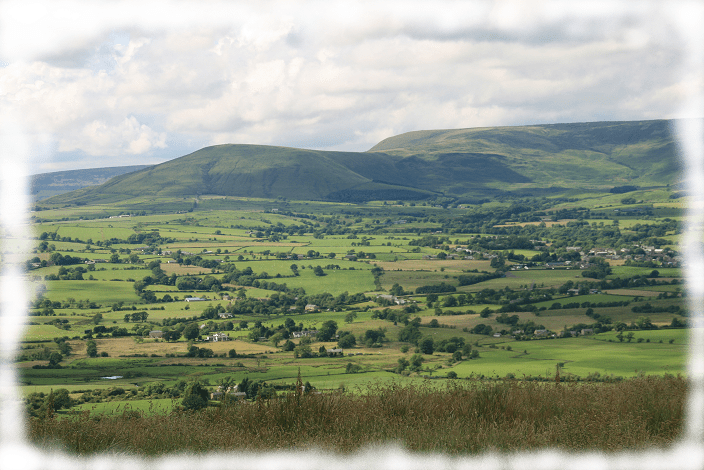

Will stared. All he could make out was a grey band. To their left was the low rolling landscape that Will had crossed on his approach. To the east and north were distant hills.

This extract from the historic novel Will at the Tower is part of the seventeen-year-old William Shakespeare’s introduction to the county and it is an ultra-concise description of the local topography. The conversation takes place on the roof of the residence of the De Hoghtons, who owned much of the land in William’s vista, and whose property was closer to the centre of the county than it is now.

Right up until 1974, Lancashire extended as far south as the river Mersey which formed its boundary all the way to Manchester and thus that city, along with Liverpool, was included in its jurisdiction. When the new administrations of Merseyside and Greater Manchester were established, the southern edge of of Lancashire’s jurisdiction slipped northwards. At the same time, the southern tip of what is now Cumbria was also relinquished. Until then, that too had been locally governed by Lancashire County Council. Also, a little ground was gained, as a wedge of West Yorkshire was sliced off and spliced on to the environs of its long-standing rival county. I’m sure there are some residents of that branch of the Forest of Bowland who will remain bitter, in denial, or are even preparing pikes.

Hoghton Tower is still standing today, and is still owned by the same family, though they are in possession of a great deal less land than they held in the sixteenth century. It is a good place, on a good day, to get an impression of the peaks and plains of Lancashire. The Tower has its own micro climate, due perhaps, to the fact that it is the first high ground the west wind meets once it has swept up the Ribble estuary.

The infamous Blackpool tower, which marks pretty much the westernmost edge of the county, is over twenty miles away, but can be seen on a clear day not just from Hoghton but from any elevated position in the county, even those as far south and east as Rivington Pike, and the nearby Winter Hill. You can spy it north of that from Longridge Fell which is the southernmost fell in England, or even further north from the Bleasdale hills, or from the iconic Beacon Fell, which is approximately at the centre of the modern county.

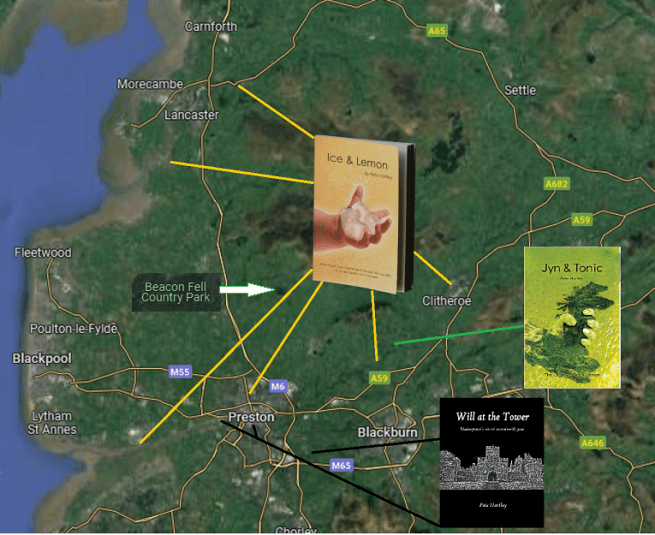

If you want to explore Lovely Lancashire, basing yourself close to Beacon Fell will not only afford you a beautifully bucolic immediacy but also put the entire county within about a thirty-mile radius.

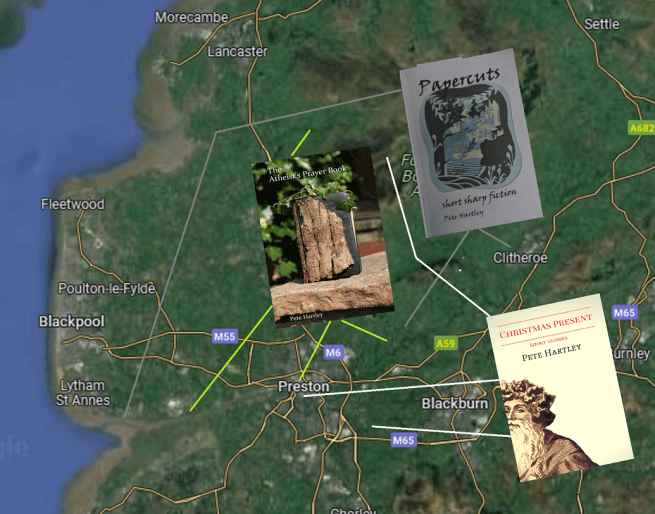

I have found inspiration in all these places. The sight of the Bleasdale hills from Longridge Fell gave rise to The View from Jeffrey a story encased in The Atheist’s Prayer Book. A prehistoric circle at Bleasdale also crept into that story as did childhood memories of camping by the river Brock and being told by a Scout leader of the ghost owl at Gill Barn, a ruin on the bank of that river.

Beacon fell is eminently explorable by persons of all ages, with its one-way tarmac tonsure, visitor centre and network of woodland paths containing hidden delights, both natural and artisan-carved.

Very close to Beacon Fell is a narrow road called Snape Rake Lane (a dead end for vehicles) which I have known since my childhood. A magical moment involving a mysterious pool and a troop of pony trekkers prompted Bridle Path which is the opening tale in the Papercuts collection of stories.

Head eastwards towards the ominous bulk of Pendle Hill, infamous in these parts for the wistful reimagining of what was one of England’s disgraceful religious misogynies – the prosecution of the ‘Pendle Witches’. That influenced Unbroken another tale in Papercuts, which was prompted by discovering that J.M.W. Turner painted a beloved half-day picnic site from my youth, Edisford Bridge, (in Turner’s time named Eadsford) which is just outside Clitheroe, a town on the cusp of the Lancs / Yorks border.

Pendle always appears morose, pensive and petulant. It squats on the landscape, a hog of solidified shadow. Mostly this is interpreted as a cask of dark magic, but maybe it is rather a mound of mourning for the miscarriage of justice founded on prejudice – as most judicial miscarriages are.

You can wind your way through one of Lancashire’s most beauteous roads by following the route that the so-called witches were forced to take to meet their show trial and unforgivable execution at the county’s eponymous city. The Trough of Bowland is a sinuous valley and high pass between Clitheroe and Lancaster.

Just south east of the lower end of the trough, Whitewell and Dunsop Bridge can be recommended, with the Dunsop valley, affording a delightful excursion into an exquisite hidden dale possible not only on foot but also by other methods of mobility.

Pause here and you are very close to the very centre of Great Britain.

Backtrack along the Ribble to Hurst Green and Stonyhurst College, a magnificent edifice with a notable history. Once the seat of the Shireburn family, it is now a public school. Cromwell slept there, as did Arthur Conan Doyle, one of the founders of the United States, and the sons of J.R.R. Tolkien – and their father. Elementary is the story that binds some of these in one narrative ring. Find it in Papercuts.

Traversing this stretch of the Ribble Valley puts us very much in Ice & Lemon territory, and that of its sequel Jyn & Tonic. The former novel will take you all around Lancashire, to Ribchester (site of a Roman fort – interestingly documented in the small but informative museum there) and to Clitheroe again, and north to Caton near Lancaster. From there the story sinks south to Garstang before cutting to the coast and Glasson Dock which is another ultra-delightful under-visited locale.

There are few places so peaceful on a summer day. With the marina before you, a panoramic arc of the Lune estuary is but fifty yards behind you, while a short stroll over the swing bridge and over the headland opens up a breathtaking vista of Morcambe Bay. See my earlier post: Glasson Clock.

Much of the first half of Ice & Lemon plays out in Preston, and Will at the Tower visits the city when it was an early modern town, with a sixteenth century coming of age happening in the historic market heart and away to the west on the river bank at Lea. The latter location is on the Blackpool Road and go that way to find the genteel resort of Lytham St Annes, a quieter and infinitely less brazen seaside escape than its more famous towering neighbour. St Annes has seemingly endless sands when the tide is out. Much renovation has taken place on this shoreline in recent years adding to its charm without unduly compromising its Edwardian appeal.

These seaside resorts bloomed like magic mushrooms as the ground-down workers of the Industrial Revolution finally gained some statutory free time. The so-called ‘wakes-weeks’ spawned mass migrations from northern mill towns providing a much-needed regenerative contrast to the degrading exploitation dressed up as dignified labour. See my father’s account of this in Fancy Weaving .

There is another even darker aspect to Lancashire’s manufacturing and recreational growth. I’ve written elsewhere of the shameful debt our region owes to those who were much more misused in order to accrue our collective, and individual wealth. See Cotton tithes matter. Our landscape bears their scars. I cannot not see them. They’re in the architecture of the mills and the weals of the hills whose valleys first fuelled spinning machines.

I touched on some of those injustices as long ago as 1986 by piggy-backing on Conan Doyle’s deductions.

Click on the pic for a closer look.

Thankfully, the regenerative power of mother nature is perpetually evident and Lancashire abounds with regrowth, sometimes vividly cloaking the industrial extravagances and reclaiming the materials of their construction. You’ll find these being progressively hidden all over the county if you know where to look.

For wildlife lovers, especially those of an ornithological bent, there are numerous enclaves where you can employ your binoculars, or open the eyes of the next generation of conservationists. Martin Mere and Mere Sands reserves close to Burscough offer wetland walks, as does Brockholes which is entered directly from Junction 31 of the M6, while, closer to Lancaster, Leighton Moss contains the largest area of reed bed in north-west England. Sitting next to Silverdale on the edge of Morcambe Bay the reserve boasts the largest expanse of intertidal mudflats in the UK.

These are just some of the places that have provoked my pen-pushing, and whatever your creative or escapist predilection, I encourage you to stop here, look, listen and imagine. Whenever you do that, you fertilise the landscape, and it finds new nourishment in your mind. Together we make a new reality. That experience is without boundaries, and never ends.

Lancashire holds inspirational seedpods in abundance. Maybe, like me, you think you know parts of it very well. But we don’t you know. We don’t.

There’s so much more to uncover than we can ever imagine.