Engine’s turning

But there ain’t no spark

Owls a-hooting

But the dog won’t bark

No more greetings

From the meadowlark

Deep in the darkest night

These were the words that came to mind on the afternoon of Sunday 13th July 2025 when, while sitting in my garden shed, I heard Bob Harris on BBC Radio 2 relate the news that Dave Cousins had died. Dave wrote the above lines following the death of his brother in 2004. The song is called Deep in the Darkest Night, and that’s the ambience I felt when I heard the news, in the mid-afternoon, with the sun blazing down beyond the window.

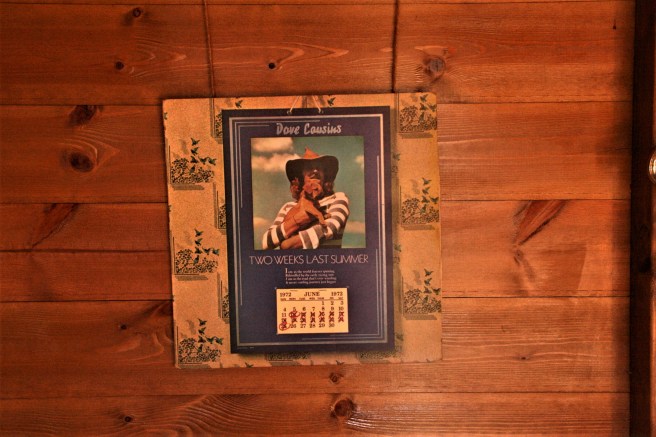

Dave Cousins, or more precisely his work, or even more precisely, his words, had been the guiding light out of the murky mire of adolescence, through the labyrinth of young adulthood, the maze of middle age and into the hinterland of retirement. I first heard his music in 1972, was firmly hooked in February 1973 and will remain tethered until the Reaper stands before me in the room.

There are many obituaries out there. I will not add to those. This, instead, will be an attempt to explain how and why his work became vital to my spiritual searching, my creative impetus, my imaginary plundering and my psychological balance. Long before we met, he made promises. He kept them.

Sleep the sleep of peace

And I will let you be

I alone can comfort

I alone can set you free

I will be your healer

And give you back your pride

In times of need remember me

At rest here by your side.

(From Blue Angel)

Throughout this post I will be using excerpts from Dave’s lyrics. They are all available in full on the STRAWBS OFFICIAL WEBSITE

In his later years Dave liked to be known as David, but through most of his sixty-year career as a singer-songwriter he was more widely known as Dave, so that is how I will refer to him.

Why was he so influential? For many reasons.

The personal

Taste is beyond our control. We either like something or we don’t. Rationalising or analysing can’t change that. I like strawberries. I also like the music of the Strawbs. (Well, 97% of it.) I like other music too, but no other music has affected me so extensively, so persistently or so profoundly. I’m sure a lot of that is down to luck, but other things played a part.

The Strawbs’ heyday coincided with my emergent adolescence. The songs were about the subjects that fascinated me emotionally, hormonally and psychologically. They were about heterosexual romance and heterosexual sex, but to my initial surprise, they were also about the politically personal, the moral, the fundamental and the unfathomable. They hit the zeitgeist. From the mid-sixties to the mid-seventies they were bang on trend. I turned twenty in 1976. They were fashionable, just when I needed them most.

The late sixties and early seventies songs of the Strawbs filtered a world view through English pastoral lenses influenced by folktales, folk song and folk-art. They were epic in an Arthurian sense or decorative in a William Morris mood, tinged with pastoral classical constituents, but totally modern in manifestation. The romantic milieu was not superficial, it was an integral code asking the questions a teenage boy wanted asking, and in doing so exposing the hypocrisy, frustrations and failings I feared. Some songs were grotesquely dark, adding a sense of existential uncertainty.

The Reaper stood before him in the room

His melancholy smile matched the gloom

He tried to rise but fell back where he lay

Tried to speak but stumbled as the sentence slipped away.

(From The Antiques Suite)

Dave Cousins knew that the price of true artistry is cruel honesty:

A man of honour has no secrets

How can I be a man of secrets?

(From Blue Angel)

The song that first sank irremovable barbs into me, remains my favourite. Down by the Sea was written as Cousins’ first marriage was on the rocks and a parallel relationship was also in treacherous waters, but I wouldn’t fully understand that until nearly forty years later when he published a commentary on all his work prior to 2010 in Secrets, Stories, Songs (ISBN:9780956588708). What hooked me was the tremendous musical production tethered to meaningful yet mysterious lyrics. Here’s the whole of Down by the Sea:

Maybe you think, a lot like me

Of those who live beside the sea

Who feel so free, so I surmise

With their comfortable homes, and wives

Who end up drinking tea together

In the afternoon of their lives.

They build their homes upon the seashore

The quicksand castles of their dreams

Yet take no notice of the north wind

Which tears their building at the seams.

In their dismay and blind confusion

The weeping widows clutch their shawls

While as the sea mist ever deepens

The sailors hear the sirens’ calls.

And in the maelstrom sea which follows

The lifeboat sinks without a trace

And yet there still remain survivors

To bear the shame of their disgrace.

Last night I lay in bed

And held myself

Trying to remember

How it once was with you

How your hands were softer.

Yesterday I found myself

Staring into space

Rather like the sailor

In my own home surroundings

I’m not sure I know me.

If you were me what would you do?

Don’t tell me I don’t need you to

It won’t help me now

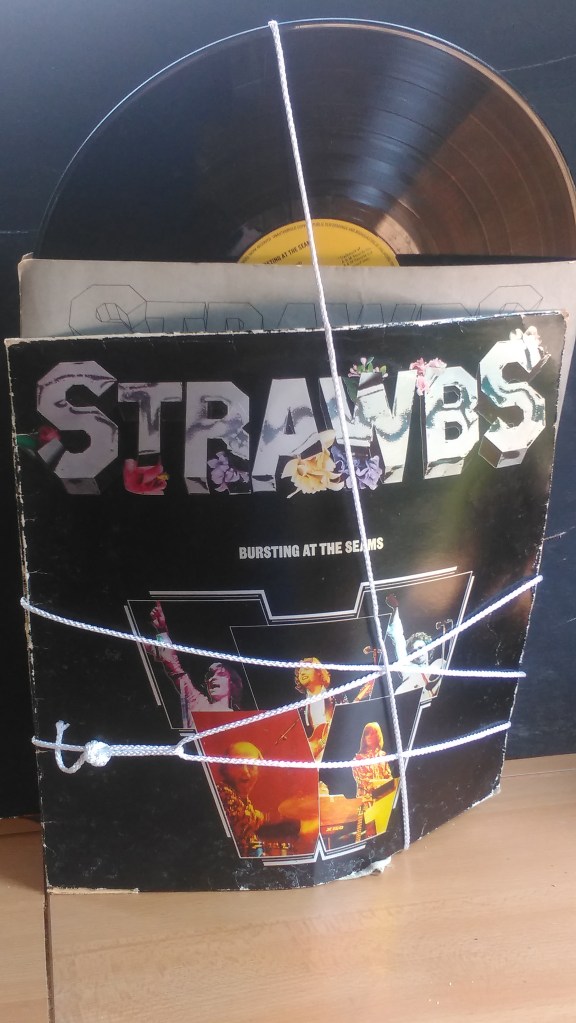

More than any English teacher, or text, this song, and its companions on the Bursting at the Seams album, ignited a fascination for the power of language. The evocation of quicksand castles, sirens’ calls and maelstrom sea was mesmerising, especially when set against titanic electric rock, but then the enigmatic sweeps in – a lifeboat that sinks without a trace, and yet there still remain survivors. How was that possible? What did it mean? And what about the question that insists it should not be answered?

This song typifies Cousins’ use of natural imagery. That inclusion is a major feature of his work and is another attribute that I found magnetic.

Natural metaphors

I became a Strawbs fan following a gig promoting Bursting at the Seams at Preston Guild Hall. I eagerly awaited their subsequent releases, but in the meantime, set about buying up their back catalogue. I began to notice threads, themes and symbols. The north wind, mentioned in Down by the Sea, was to be found four albums earlier, rather oddly I thought, bringing with it the eponymous Dragonfly:

The dragonfly appeared

The north wind brought it by

As summer slipped away

And autumn was approaching

And that wind is waited for again at the end of the song:

And now the warmth of the pale winter sun

Has melted the heart of the snow

I lie awake throughout the night

And wait for the north wind to blow.

A southern, westerly or easterly wind might bring a dragonfly, but of all winds the north seems the least likely. I had to wait four decades for the full explanation. The Dragonfly was a Swedish woman. The north wind, it seems, is that aspect of fate that brings a chill to challenge our emotional comfort. Perhaps it is even the breeze of infidelity. Cousins remarks in Secrets, Stories, Songs that the Dragonfly left its Swedish habitat to alight briefly in Copenhagen in the notes accompanying the intimately explicit lyrics of Fingertips. Copenhagen, where the Strawbs played and sometimes recorded, is south of Sweden. The Dragonfly first appeared in Cornwall he says. Cornwall is also south of Sweden.

Note again, the north wind’s appearance down by the sea, when the quicksand castles are torn at their seams. Whilst all this was unclear at first, second, and five hundredth hearing, the pattern had been spotted, the enigmatic lyric had lassoed my interest. Cousins uses the wind a great deal. The west wind appears to be the most prevalent, used in its traditional sense (for the UK):

The roses stoop lower

As their petals fall.

So shall our love die?

“What is it,?”

She says.

“Nothing,”

Say I,

“Nothing but the west wind,

The wind of change.”

These are lines from So Shall Our Love Die another song charting the fracturing of a relationship. This one has a happier resolution as celebrated in Tokyo Rosie:

The blossom has fallen before the west wind;

The butterfly lies with its silken wings pinned;

Alone in the temple the lovers rejoice

And sing to each other with one single voice.

I wear my silk kimono black,

Get your monkey off my back.

No matter where the west wind blows,

You’ll never find a fallen rose.

The flowers of heaven are roses in bloom;

The east wind turns west in the walls of my room.

I build my defence in the palace of sin,

The lovers make home and the loser must win.

Nature abounds in the Cousins canon. Hills, forests, plains, gardens, cliffs, beaches and witchwoods provide a bucolic backdrop while flora and fauna flourish. We are in among the roses, wandering far on the lonely moors (where Dave turned his face into the wind), down in Devon catching a glimpse of heaven, or beginning another day in Cornwall, as crabs scuttle awkwardly, shyly away and gulls soar on the breeze like marionettes with invisible thread. Elsewhere the foxes fear the hunters, bats replace swallows and dogs snap at the heels of sheep. A peacock looks dejected. A snake, a wolf and an eagle do nightmarish things in The Vision of the Lady of the Lake.

In the songs, as in life, the natural sometimes disguises the reality. It can appear delightful but also ominous, or worse.

The witchwood started singing

With a strange unearthly sound

My fingers grew like branches

I stood rooted to the ground

And the spell is still unbroken

I am still her bidden slave

Till a casket from the witchwood

Bears my body to the grave.

(From Witchwood)

Of all the natural images, perhaps it is The River that, by its very absence, churns the strongest.

I made a sideways motion

Turning a new leaf

The single-minded miner’s girl

Was there to share my grief

I shivered in the bitter wind

Three times the cockerel crowed

I waited for the river

But the river did not flow.

There is the wind again. No direction is specified, but played live the song usually led directly into Down by the Sea. As a good Catholic boy baptised Peter, I didn’t have to think too much about the thrice-crowing cockerel, but what river was this? Why wouldn’t it flow? Cousins says in Secrets, Stories, Songs that this work summarises the breakdown of his marriage, “the river that had been damned by deceit”.

Cousins had shown me how to turn the personal into the universal. He made the private public without betraying his sources. I could not know the facts that had inspired such intimate angst, but that didn’t matter. I detected the potency and the integrity of the pleas. They were delivered with finely tuned theatricality, sometimes understated sometimes with magnificent melodrama, yet always resounding with truth. By hunting for the hidden meaning, I could find my own values. I could realign the content to make sense of my own experiences, hopes, fears and fantasies.

And so, we return to the sea, perhaps the most dominant natural phenomenon in Cousins’ nature imagery. It is there illustratively but also metaphorically for the stormy, the calm, the uncertain, and the unconquerable. It is something to take a trip across with Miss Columbus, and the place where Hero must sail all alone to die. It is often mysterious and allegorical as in Queen of Dreams:

Spoke the Queen of Souls

I was lord of the ocean

Swam beneath her waves

Sheltered within her shipwrecks.

Is it any wonder that a sixteen-year-old Lancashire lad wanted to stay in the deep water? Meanwhile, across the Irish Sea, brothers were executing each other.

The political

The Strawbs had played in Belfast before ‘the troubles’ erupted which made the horror of the sectarian violence even more raw for Dave Cousins. As a consequence of his father dying in a submarine during the war, and his mother remarrying, Dave’s half-brother was brought up a Protestant while Dave was indoctrinated as a Catholic. Had they been in Northern Ireland they could have found themselves on opposite sides of the conflict. This coincidence gave rise to one of Cousins’ best-known songs The Hangman and the Papist.

The hangman sees his victim

And the the blood drains from his face

He sees his younger brother standing proud

This track on the From the Witchwood album and New World from the Grave New World album punched hard at the political bigotry and incestuous cruelty of the conflict.

How can you teach

When you’ve so much to learn?

May you turn

In your grave

New World

These were just two of the many songs in which Cousins attacks violence, and in which war is denigrated or is the cause of lamentation. The Battle on the first album is ostensibly just a game of chess but the post-carnage description is visceral. The Weary Song which opens Dragonfly on one level is an elaborative fantasy of leaving a family, but within the military narrative cuts truthfully deep:

The soldier smiling softly sings a song of sad farewell

As the train pulls out to take him far from home

His children waving gaily without knowing he has gone

Now you know how I feel.

He was not afraid, much later, to apply the same treatment to terrorism in The Broken-Hearted Bride:

He caught the train that morning

It was overcast and grey

He waved and blew her kisses

There was nothing left to say

He pulled the cord inside his coat

And blew himself away.

He also responded to conflicts in former Yugoslavia (There Will Come the Day), Afghanistan (Where Silent Shadows Fall) and in the air (Hellfire Blues). The Pro Patria Suite from the Dancing to the Devil’s Beat album is a very moving Great War tribute, but it was the contemporary clutch of 1970s songs responding to the Irish conflict that cemented my affinity with the band.

The songs of protest, condemnation and derision made the political personal, which is what it often pretends to be but seldom is. They energised my sense of injustice and hypocrisy. They sharpened my analytic pencil.

The lotion

The combination of the penetrating words and the all-important accompaniment enlisted me. I realised how the music became the carrier and the preservative of the words. Whether the songs be about love or war I would not have heard or read the words, without the application of the music. The words were the active ingredients; the music was the lotion. It took me firmly by the arm, and I was addicted.

The philosophical

Love and war had enrolled me, but above and beyond both of those, it was the philosophical and religious that confirmed my conversion.

My Catholic faith was embedded in my soul, but my humanity had questions, and they were inadequately answered by those I thought should know better. Cousins showed me that I was not alone. From Lay a Little Light on Me:

Watch my hand

See it shakes

Trembling as my life blood bleeds

Comfortless

Superfakes

Offering their empty creeds

That have no faith or substance

That change to suit the doubter

To satisfy his needs.

I didn’t want to be a doubter. I couldn’t help it.

Growing boys

Masturbate

Drink the wine and take the bread

Saintly priests

Castigate

Holy water for the head

With shades of John the Baptist

Who came intent to rescue

And danced with death instead.

Rid me of your darkness

Lay a little light on me

Clothe me with your brightness

Lay a little light on me

Oh save me someone

Lay a little light on me

I didn’t want saving. I had repeatedly been told I was born saved. I was also told I had been born a sinner. That cruel contradiction made no sense; and no one could explain it. Not even Dave Cousins. But he could help with the calling out.

Bless the good

Curse the bad

Some are wise

Others mad

Phoney profiteers suitably seeming sad

Preparing for the kingdom

Anointing us with wisdom

Convinced that we’ll be glad.

The use of ‘profiteers’ is typical of Cousins’ poignant wit.

One of my favourite songs then, and now, was and is Hanging in the Gallery.

Is it the painter or the picture

Hanging in the gallery?

Admired by countless thousands

Who attempt to read the secrets

Of his vision of his very soul.

Is it the painter or the picture

Hanging in the gallery?

Or is it but a still life

Of his own interpretation

Of the way that God had made us

In the image of His eye?

This perfectly summed up my thoughts on the role of artists, regardless of their discipline, and while the first verse acknowledges the influence of the concept of the supernatural creator, the second puts the creation of truth firmly in human hands:

Is it the sculptor or the sculpture

Standing in the gallery?

Touched by fleeting strangers

Who desire to feel the strength of hands

That realised a form of life.

Is it the sculptor or the sculpture

Standing in the gallery?

Or is it but the tenderness

With which his hands were guided

To discard the unessentials

And reveal the perfect truth?

My faith journey was not entirely guided by the work of my favourite band, but their music kept me marching on. It seemed that my evangelist of choice may have been on a parallel pilgrimage:

I prayed to my God for guidance to find there was no-one but me

There was just the open highway as far as my eyes could see.

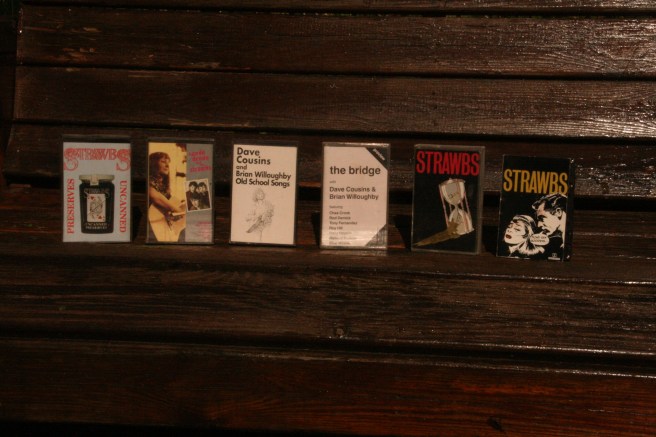

That revelation came many years later in The Plain from the Cousins and Willoughby 1994 release The Bridge. (Also to be found on the Strawbs’ Blue Angel album of 2003.)

Cousins’ writing was the first avenue that enabled me to confine the everlasting in the moment. They were the first gospels to lead me to make sense of our existence by realising that our existence does not make sense and is certainly not convincingly explained by ancient texts, or those who perpetually reinterpret them.

Dave’s New World

I’m eternally grateful to my schoolfriend Michael Holme who asked me if I’d like to accompany him to the Strawbs’ Preston gig in 1973. The next day I went out and bought Bursting at the Seams and Dave Cousins began to show me his world in a manner that made me start seeing mine from a different point of view. That’s what great artists do; show you the world anew or at least ask you to look again. I looked, listened, read and re-read the lyrics on the record inner sleeves and spent endless sofa-bound hours thinking, considering, imagining. The world changed; or perhaps it was just me.

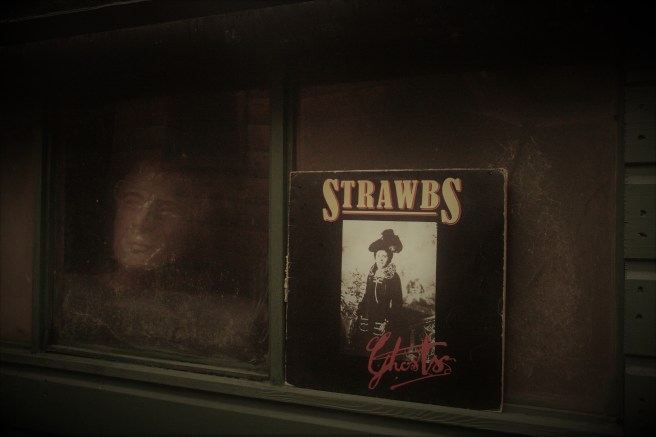

It was very gratifying to read Secrets, Stories, Songs and Dave Cousins’ autobiography Exorcising Ghosts (ISBN:9780956588715), and finally have some long-standing mysteries at least partially solved, but in one sense it was also disappointing. Knowing the truth behind a song clarifies a meaning but also limits it. The less we know about a piece of poetry the more we can make it our own, and that surely is the poet’s greatest gift. Thankfully, there is still a great deal of lyrical mystery in the Cousins canon to allow that diversion. All diversions lead astray he wrote in Benedictus. Maybe, but sometimes going astray is the best way.

Whether Cousins’ songs deal with the religious or secular there is always an element of the philosophical. That, above all, is why I crave them. I have never found that level of the metaphysical expressed so consistently or so tastefully in the work of any other writer. That is why Cousins is my hero.

I care not about the nature of the man himself. I met him on three or four occasions, after gigs, but I did not get to know him personally, and I am glad of that. It is the work I love. It is the poetry not the poet hanging in my gallery of the invaluable.

You only need to listen to his songs to know his private life was not always plain sailing, and if you read Secrets, Stories, Songs or Exorcising Ghosts you will see his professional life had its fair share of troubles. Without those sufferings we would not have the most moving of his poems. In 1973 I needed the work of artists who were flawed. How else could I find a companion to follow on a never-ending journey just begun?

I’ve nothing more to give said David Joseph Cousins in I’ve Been My Own Worst Friend:

Like the sand I’m high and dry

I’ve no more dreams to weave.

But if pleasure means money, then take it all

I’ll make sure I’m out the next time you call

I know that something always turns up in the end

I’ve been my own worst friend.

Creatively and philosophically speaking he’s been my best friend. I never got to know him, but I think I know what he means. I certainly know what he means to me. In 1972, he wrote an intimate promise to his Blue Angel , and then was generous enough to make it available to us all:

When the hour of darkness comes

And time itself stands still

When voices from the future

Seem to come and go at will

I will be your servant

Your ever constant guide

When all is lost remember me

At rest here by your side.

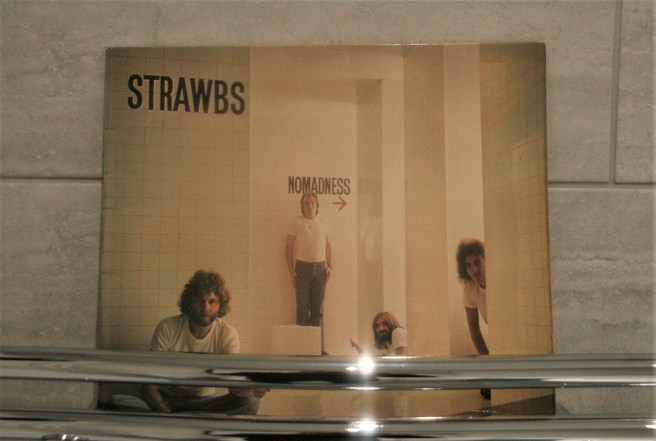

If you want my wider thoughts about the Strawbs you can read my earlier posts starting with Savouring Strawbs which contains a summary of their recordings and recommendations for getting a foothold on their music.

I followed that post with individual appreciations of each of the first dozen or so albums from 1969 to 1978.

I may well now pick up that tendril and deal with the remaining works. Watch this strawberry patch.

2 thoughts on “Dave Cousins: poetry in lotion”