Gertie and the Guild Machine: making a play for kids

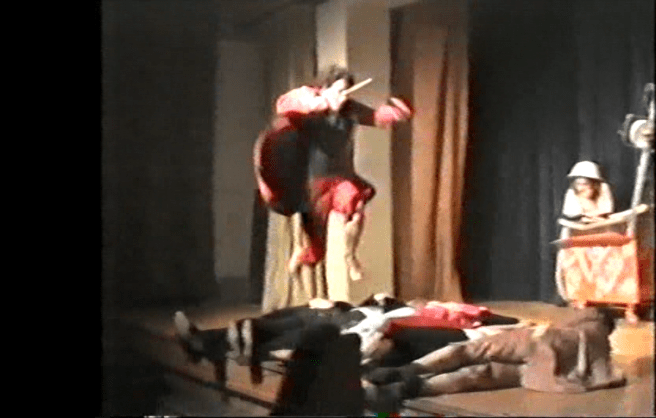

How do you make four thousand children laugh? Easy. Fall over. This is an abiding memory from three decades ago when I was charged with writing, producing and touring a play for children. It is second only to the breath-holding fear when eleven-stone Gareth launched himself over a carpet of tiny volunteers in a gut-threatening leap during the climax of a sideshow sequence. I’m not sure we’d be permitted to include that manoeuvre today. The risk-assessment would probably preclude it.

Apologies for the quality of some of the pictures. They are screenshots from a copy of a copy of a VHS tape from the last century.

The thrill came from laying two or three actors side by side while Gareth leaped over them, then repeating the action after adding two, three, four or more volunteers from our audience of children. We always concluded, upon reaching seven or eight bodies, by sticking Carl, one of the two principal performers, on the end. Gareth, who was a gentle giant in real life, and keen on martial arts, never failed once in twenty-nine attempts, including one on the proscenium stage of our home venue where his run-up was precisely three steps.

Understandably, the feat invariably drew a great cheer, as well as a huge sigh of relief from the whole cast, especially Carl. It was Carl who generated the most laughter by falling over at frequent intervals. I was puzzled then, and remain so now, as to why children in particular find falling so funny. It seems to be innate within us. It is typified by the banana-skin cliché. Its functioning was explained by one of my heroes Keith Johnstone (See: The man who wrote the book that changed my life has died). All of Drama, and pretty much all of human interaction depends on negotiating the see-saw of status. If someone’s status is seen to fall then, usually, our own rises in comparison. It makes us feel better, or superior, or more fortunate. So much of human interaction derives from that transaction. We look upon history with what is often a simplistic view of hierarchy. Status rules. It always has and does so more than ever today. Check your phone.

Gertie

Gertie and the Guild Machine was commissioned by Preston Borough Council in 1990 for one very simple purpose. The town (as it was then) was on the cusp of the next Preston Guild festivity. The Guild, as it is known locally, is a year-long celebration of the trading charter, which was granted by King Henry II in 1179. These days it is held every twenty years, with the next one due in 2032. Events are held throughout the year but culminate with a two-week carnival, usually in September. Of course, anyone under the age of twenty has no recollection of the previous Guild, and back in 1990 it was not quite so simple to access and share recordings of earlier Guilds. The council thought it prudent, therefore, to commission a play that could be toured around junior schools so that the children might learn about the history of the Guild and be enthused to take part in the next one.

The play was performed by a dozen students from Limelights, the recreational drama group at Newman College. We toured twenty-seven schools and added a couple of shows in our own college. It was seen by over four thousand children. Their reaction was palpable. Child audiences are never subtle. Their enjoyment was plain to see and even plainer to hear. I have no way of knowing if they went on to contribute to the 1992 Preston Guild in keener or more meaningful ways than they otherwise would have, but they learned a little local history, and were hopefully tempted to witness more live theatre, and maybe even make some of their own.

The challenge

The task was simple. I had to find a way of condensing eight hundred years of local history into half an hour, while stringing together a story that would grab the children’s attention and excite their imaginations. Simple? Well, not really.

The Guild concept was riddled with archaic terms, many of which were integral to understanding what was going on and why it was happening. Let’s start with the title. What is a Guild? It is, of course, a federation or collective or union, but the children didn’t know that (and neither did a good deal of adult Prestonians) and children didn’t know what unions, collectives and federations are for. To further confuse the matter, we were going in to their assembly halls to talk about the Guild, which is a kind of guild of guilds. Even more confusingly it is often referred to as The Guild Merchant, even though some of the Guilds within the Guild are merchants, such as butchers, fishmongers, greengrocers, brewers, tanners, costermongers and cordwainers. I’m sure you know what costermongers and cordwainers do, or did.

Theatre comes to the rescue at times like that. An actor in an apron looking admiringly at the shoe he is holding needs very little dialogue to convince a child that a cordwainer was a shoemaker. We strung together a whole sequence of such identifying instances whilst weaving them into a straightforward time-travel tale.

Every leap helps

A supermarket trolley was – er – acquired and adorned with a few prop items and switches and dials donated by the science department. This became the Guild Machine, an invention of a curious old woman with a penchant for previous Preston Guilds. The intrepid young Gertie and her pal Chippi got the chance to try it out. Off they went, she inside, he sitting on top, whilst leaping back and forth through history but only ever arriving in Preston, and at a scheduled Guild time. The machine was hurled around the performance space at great speed by the aforementioned Gareth, in the role of a Town Crier. He always stopped far too suddenly, catapulting the hapless Carl to the floor, triggering merciless laughter.

Note that their arrival was always at a scheduled Guild. Sometimes there was no celebration to see, for example in 1348, when the plague was in town. We were not afraid to include contrasting moods. (More recently, Preston Guild was postponed for a decade because of World War Two.)

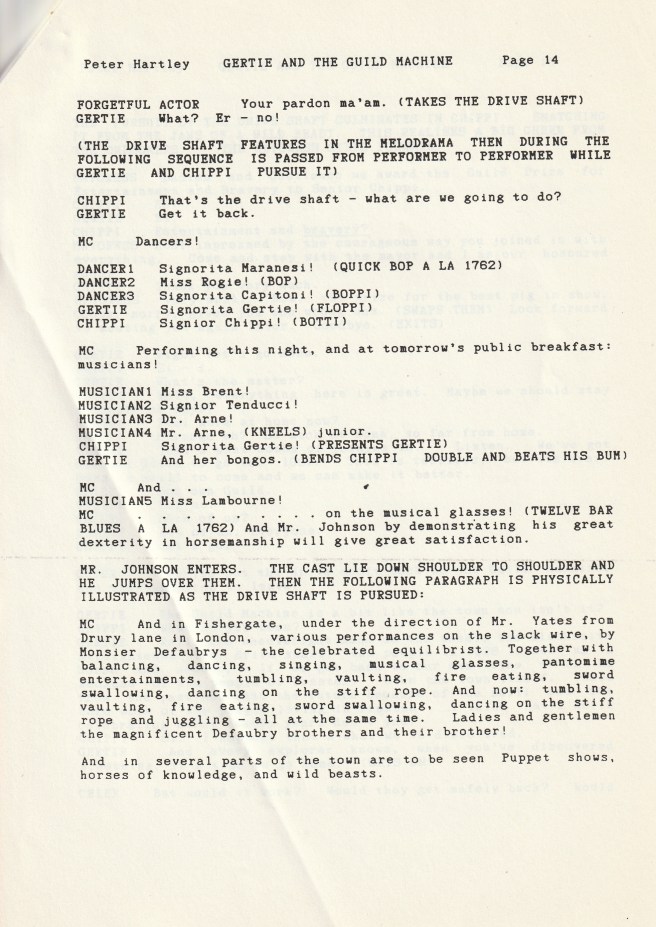

Great fun was had by our protagonist and her pal, but things did not always go to plan. The Guild Machine crashed, stranding Gertie and Chippi in 1762, but a combination of their courage and determination and the skills of previous Prestonians, resulted in repairs being made.

Pre-wokeness

We did our best to be ahead of the curve with respect to inclusivity. For historical reasons, the college, at that time, was predominantly white. I had attended the sixth form of one of the three forerunner institutions just fifteen years earlier. (See: Hard Terms) I still have the photographs of all of us who enrolled when I did. There is not a single non-white face among them, and narrowness still prevailed in 1990, though things got much more diverse quite rapidly after that. We had zero diversity among the cast, but I was acutely aware that the schools we were to visit had a much richer mix. I was determined that the lead character should be female and that a principal performer should have a contrasting heritage. I was certainly not going to resort to make-up or stereotypical mimicry, even though both those techniques were deemed acceptable on broadcast media more than a decade later.

It transpired that Carl could pull off a passable Italian accent, so we played to that strength, though this led to the only act of censorship imposed on the script. Chippi, was initially called a coward (he wasn’t one, in fact his bravery saved the day) but Preston Borough Council insisted the references be changed to “not very brave”. To call Chippi a coward was deemed a slur on all Italians, which was not intended, nor was it true in the story, but there we were. The change was made. Chippi was a not very brave, very brave little boy.

What did we learn?

Child audiences are no different to adult audiences. They want to be entertained. The secret to that lies in the mantra that theatre is a visual medium. Keep the eyes happy and the ears will attune. I now believe that literature benefits from the same approach, though in that case it is the mind’s eye that must be pampered. (Drama and literature are miles apart. See: Reading without the room) We kept Gertie fast-moving and intensely visual at all times, even though we had very limited resources. We had a company of twelve, some rough costumes, a few props, a very basic light and sound system and a shopping trolley. We left college just before lunch, travelled to the chosen school, set up, performed, packed up and returned to college just after lunch. By necessity, we had to be compact in all respects.

We kept the dialogue minimal but did not fear introducing archaic references, always ensuring we illustrated them with clear actions, and where possible, humour. This is equally effective for adult audiences. Humour is a much-underrated stimulant.

We employed a great deal of direct address to the audience. This technique has been part of theatre since ancient times, though it has sometimes been out of fashion. I have invariably found it invaluable. It rarely works on the screen as part of drama, but it is supremely effective in live theatre where it becomes an umbilical cord. It sustains the flow of aesthetic contextualisation and constantly reminds the audience that they are in the same time and place as the performers.

Time and place was the point of Gertie and the Guild Machine. It is, I suppose, the whole point of the Preston Guild celebrations. Different time, same place. We owe everything to the past, and bequeath what we do, to the future. We should, therefore, do what we do, as well as we can.

The first read through of Gertie and the Guild Machine was during the college dinner break on Monday 23rd April 1990. The play went on tour in June of that year with performances continuing until the final week of January 1991.

A small section of the play was revived and included in the Cardinal Neman College summer musical of June 2010: Once Upon a Preston Guild.

I will be contributing to more discussion about writing for young people, later this month at Chorley Little Theatre:

One thought on “One Giant Leap for Childkind”