A huge round of applause for Joan Littlewood.

If you have ever enjoyed, or suffered, a creative workshop, then you must thank or curse Joan Littlewood (1914 – 2002), for it was she who coined the term in 1945:

I wrote it across my diary. ‘The Workshop’. A theatre, a workshop? Everybody made fun of it, but years after, ‘Workshops’ sprang up all over the place. Everything was a Workshop, from two councillors meeting in a pub to a baby show.[1]

I’ve just finished reading Joan’s autobiography for the third time. That’s not strictly true. The first two times I only read selected chapters. In those days I was teaching full time and reading slots were at a premium. Joan’s Book is a mighty tome running to almost 800 pages, and being a biography it is not just about her theatre exploits, which is what I was primarily interested in at the time. It is a fascinating read if you have an interest in the cultural history of (mainly) the UK. If your focus is more tightly on theatre, it is less enlightening than you may hope. Although frequently outlined, her methods are only superficially referred to, with the most revealing passages being chiefly at the end.

Joan would be the first to admit that the ground-breaking activities of the Theatre Workshop were the result of collective creativity, and not just down to her. She became the face of it and was throughout the prime mover, but her lifelong companion Gerry Raffles (1928 – 75) was almost as crucial. He joined the company as a teenager quickly becoming Joan’s closest collaborator and then her personal partner. Following his death, Joan never directed again. Gerry, as well as acting, became a crucial manager and producer, constantly seeking solutions to staging problems and hunting for funding and places to play, including on national and international tours.

The Theatre Workshop was treated with great suspicion due to the left-wing sympathies of the majority of the members. Joan was under surveillance by the security services for a while and temporarily banned from working at the BBC, which was an important source of income for her. A social conscience was always at the heart of Joan’s work, but it was her belief in ordinary people being able to rehearse truthfully, portray accurately, and – most of all – collectively create that rattled the cages of the conventional.

A lot of her pioneering approaches and methods have become integrated into modern theatre practice, but when Joan and her team began, they were not only new, but considered unnecessary. In conventional theatre contributors had prescribed functions, whereas Joan blurred those boundaries. Everyone could contribute to the creative process and anyone could do whatever was required off stage. The performers would do frequent classes in movement, dance, singing, improvisation or whatever was thought beneficial. Actors did work from scripts but the development of the play was made in rehearsal. The text could be radically revised and plays could even invented from scratch by the team. Within reason, the performed text could be fluid, allowing differences in performances and the freedom to respond to interjections from the audience. Arguments in the fictional drama became arguments in the actual theatre.

Although not acquiring their famous Workshop moniker until 1945, the players had been in action since 1934 when Joan dropped out of RADA and joined up with Jimmy Miller, who would later become well-known as the Folk singer/songwriter Ewan McColl (father of Kirsty, who is best known, perhaps, for duetting with Shame MacGowan on the Pogues’ perennial Christmas hit The Fairytale of New York). Jimmy Miller and Joan Littlewood were married for a time.

Other recognisable names to feature in the ranks of Joan’s theatre group include Richard Harris, Barbara Windsor, Victor Spinetti, Brian Murphy, Harry H Corbett, and Yootha Joyce. Composer/lyricist Lionel Bart was with the company prior to his momentous success with Oliver! Prominent playwrights included Brendan Behan and Shelagh Delaney.

Delaney’s A Taste of Honey was a massive break for a writer who had only stepped inside a theatre for the first time a fortnight before she wrote it. Joan Littlewood describes how she and the workshop team had to heavily cut, adapt and embellish the script to make it work. Delaney took a lot of plaudits, but it is clear that without the full Theatre Workshop treatment it would have been a disaster. Similarly, with Brendan Behan’s The Quare Fellow, the playwright submitted a script with significant flaws, and it was the collective genius of the production team that made it work. Despite the stratospheric rise of their profiles both playwrights struggled to sustain a career afterwards. It was the Workshop that wrote the magic.

At the core of Joan’s method was improvisation. By using intensive exploratory exercises actors with little or no professional training were able to touch and expose the truths of the human condition. The reason is simple: they were human beings. Why then were such truths often not revealed, indeed frequently disguised, by conventional acting and production? Because the theatre had become a machine of deception. Even the buildings themselves were designed to deceive and hide, with spacious wings, tall fly towers, trap doors and multiple drapes. Joan was one of the pioneers of breaking through, or better still, dispensing with, the proscenium arch. Not only were actors and audiences brought closer, the latter were actively encouraged to interact with the former. Conventional actors would often please audiences in a way that drew attention to the acting, not the humanity it purported to be. Joan would not tolerate that.

Joan Littlewood began making theatre long before equal opportunities were deemed desirable. There were hardly any female impresarios, producers or directors. She was a real pioneer, and bloody-minded enough to make it work and make her way, against all the odds.

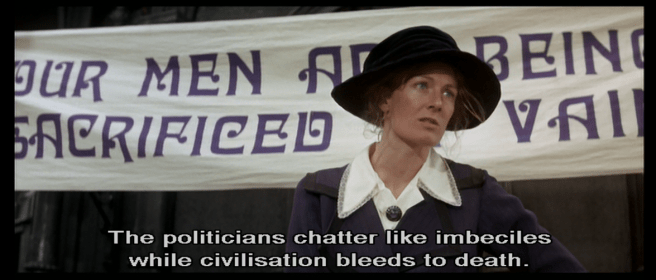

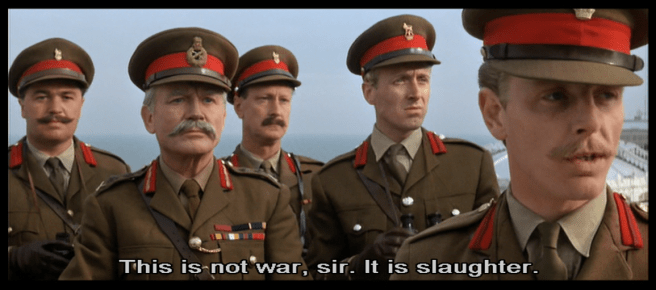

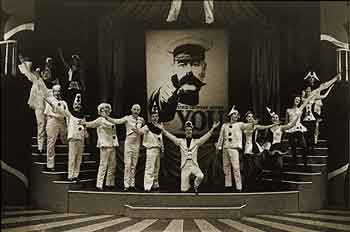

The best-known, and to my mind, the most important Theatre Workshop show, was Oh, What a Lovely War. Gerry Raffles heard a repeat broadcast of Charles Chilton’s radio musical about World War One: The Long, Long Trail. Chilton’s name is still associated with Oh, What a Lovely War, but the play is almost entirely a result of the Workshop process. It is one of the finest anti-war works of all time, and it is easy to overlook how controversial it was when first produced in 1963. The title alone was provocative, and it is crucial to realise that there were many veterans from the Great War still alive, not to mention those from World War Two and the other conflicts of the first half of the twentieth century. The Workshop triumphed again. Why? Because the core content of the songs and irreverent humour were written in the trenches by the veterans themselves. Littlewood and her team simply told the truth. Joan waged war on war in ways never seen before.

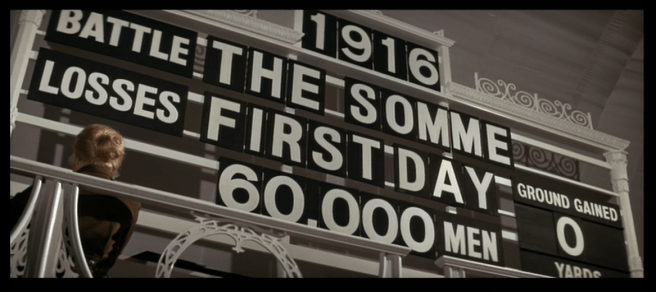

Joan dressed the soldiers as Pierrot clowns. She hated the khaki uniforms and all they stood for, and wanted the audience to leave laughing at the vulgarity of war after watching the sad clowns singing humorously about their inescapable predicament. Gerry Raffles acquired a huge news panel, a spectacular precursor of the giant screens so common today. The soldiers’ light-hearted ditties were set against the abominable losses of troops for pathetic, and often zero, gains in territory.

The luxury, idiocy and brash decoration of commanders and leaders was shown in all its intrinsic hypocrisy. The whole debacle was dressed initially as a kind of public parade. This was shown spectacularly brilliantly in Richard Attenborough’s film adaptation by using Brighton’s West Pier. Attenborough, dressed the soldiers in period uniforms, and unlike Joan, did not avoid depicting deaths. He also promoted the comma in the title to an exclamation mark.

In the earliest days, Joan’s theatre company often lived hand-to-mouth and I mean that literally. They sometimes had no money and not enough food. They would hitch-hike to their destinations and perform, or lead creative sessions, in dire premises. In winter they were cold. By the end of her active career Joan was jet-setting between projects in London and Morrocco. The company had progressed from pilloried obscurity to critical acclaim. The Theatre Royal in Stratford (east London) was rivalling what Joan described as ‘the other Stratford’ (upon Avon). By the 1970s Joan was championing a people’s ‘Fun Palace’: an entertainment venue way ahead of its time. That flexible creative and educational space was so adventurous that it failed to be realised, but it did inspire subsequent projects and the kinds of cultural experiences now common at festivals.

Not all Joan Littlewood’s projects were successful. She had her failures and continually monitored shows to reverse any decline in standards. There was an arrogance to her that sits awkwardly in opposition to her professed egalitarianism. Friends and collaborators were not always fans. In the foreword to Joan’s Book, her long-time assistant, and subsequent biographer, Peter Rankin accuses her of getting her own way ‘again, as usual.’ She dismissed the traditional view of directing, and said that she hated ‘acting’ by which she means the pretence that can all too often be seen and which cloaks the truth of the character. She claimed her only contribution was to ‘grow’ a show, but by doing so, in the ways that she did, she redefined directing and producing, and rejuvenated acting.

Joan may have lost a few – just a few – of her cultural battles, but she won her lovely war: a war against the false, the fake and fraudulent in performance.

Let’s keep her flag flying.

Here we are over a century after she was born and half a century after she stopped ‘growing’ shows. Yet men still sit in luxurious opulence, and from a safe distance, unleash ton after ton of munitions on the heads and homes of people hundreds of miles away. War is for clowns, said Joan. Tearful Pierrot clowns.

Joan would not want you to revive her show if you could make your own. War is not over. We need yet another lovely campaign.

Sadly, I fear we always will.

References

[1] Littlewood J, Joan’s Book, Methuen 2003, (ISBN: 0413773183) p 158

Similar posts

I was reminded of Joan Littlewood’s methods while watching a recent performance by Mikron Theatre as described in How Jennie Lee opened the door for you and me. Joan met Jennie relatively late in their respective careers. They were not overly impressed with each other even though there were many similarities in their social aims. Joan did not get the backing she was looking for.

If you would like to wage your own theatrical campaign, this might help:

Find out more here: Drama: what it is and how to do it.