To conclude year of re-grasping the Gothic, this is how a long-buried play spawned a new haunting

The Modern Gothic year is almost gone. The stories within will live on. I’ve spent much of this year returning to Gothic influences to provide some context and background for my story Livid, which is my first work of notable length to find its way into publication by another hand for some time. Its fiction emerged from a blend of the imaginary and the actual. This is how it happened.

Hooked by the very first line

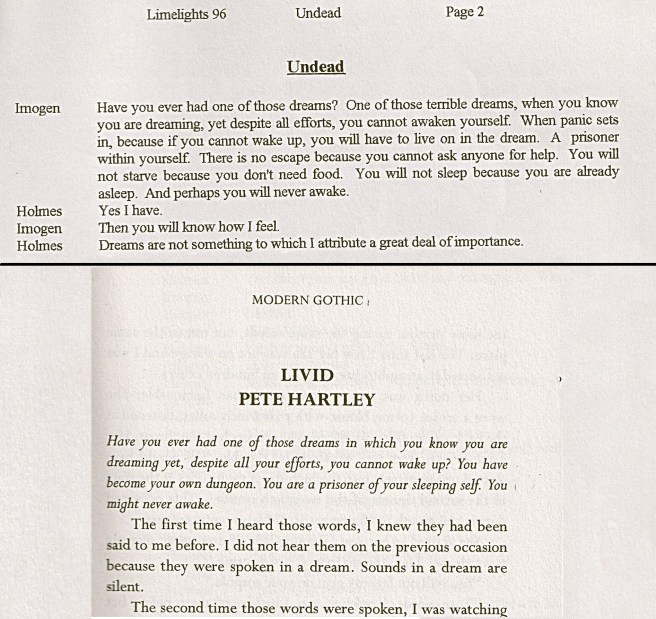

It always starts with a haunting. A new work of fiction has a kind of ghoulish gestation somewhere deep in the labyrinths of the mind. ‘Livid’, a story written for the recently released ‘Modern Gothic’ anthology, was no exception, but this one had a perceptibly solid beginning.

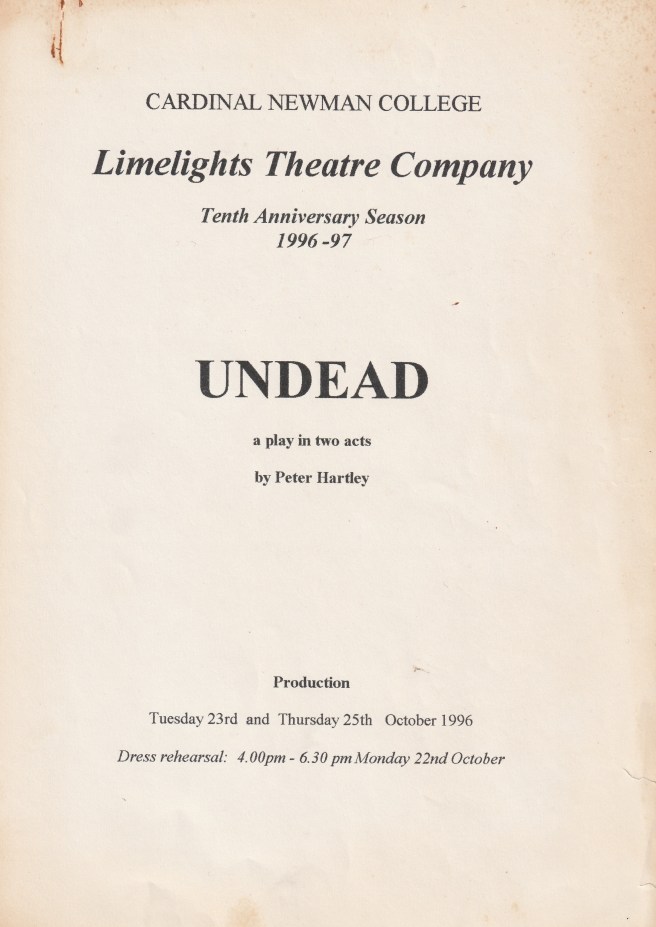

I can date it precisely to the evening of 23rd October 1996. I was watching a play I had written for a class of drama students at Cardinal Newman College in Preston, Lancashire. A single spotlight came up on a lone woman who began a short speech addressed directly to the spectators. It felt as if the whole audience – just briefly – held a breath. They had recognised something in it. That opening speech and the first paragraph of Livid are very similar.

I had written the play entitled ‘Undead’ for a group of students who were keen on the Gothic genre. I’d been writing drama for about fifteen years, but this was the first time that I felt that I’d hooked the audience with the opening line. It smouldered at the back of my mind for nearly three decades, but never with sufficient potency to live again. Then I saw a request for Gothic story submissions and I decided to dig out the old script. I must stress that, with the exception of the first paragraph and some costume detail, the play and the story are entirely different.

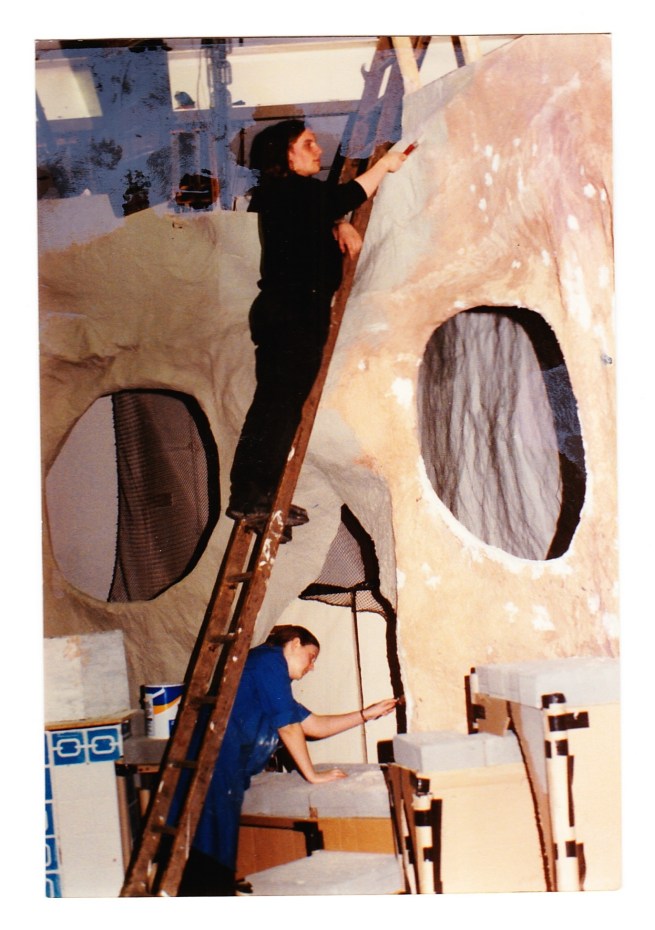

The play was very much tongue-in-cheek (or canine-in-jugular) but, as always with my theatre productions, atmosphere was paramount, so we rebuilt the auditorium right up tight to the proscenium arch and constructed the interior of a giant skull as the set.

The idea was to position the spectator inside a huge cranium, which also doubled as a tomb. Bizarrely, I’d just curated an art exhibition which included the recreation of a gents’ public lavatory generously plastered with hair. The artist (from the University of Central Lancashire) did not want it back and we reconstituted some of it as a sarcophagus.

I felt it needed the effigy of a child on the lid of the sarcophagus. Fortunately, my six-year-old son was keen to volunteer as the model. A jolly bunch of students gathered round our kitchen table with buckets. We wrapped Rick in clingfilm, covered him in plaster of Paris and, when set, he became part of the set.

The play was great fun, and went down very well, but I always felt that opening line deserved resurrecting.

Squaring the Magic Circle

It’s strange how the subconscious knits diverse strands of memory together. Fifteen years after the Gothic play at Newman, my co-producer and I took our Uneasy Theatre fringe company to Hoghton Tower with a play about the teenage William Shakespeare. A member of staff there told us she had previously worked as a magician’s assistant. She did not break the Magic Circle confidentiality code, but said enough to make me realise that the ‘assistant’ was not only the hidden power behind the magician’s throne, but also the battery pack concealed within it. Without her, he was virtually powerless. This became the plot engine of ‘Livid’.

Saw doctors and tram shelters

‘Livid’ is not set in a specific town but in my mind, it is a place not unlike Edwardian Preston. I read somewhere that Preston used to have a Sawdoctor Street, (there is a Surgeons Court that runs parallel to Fishergate across Fox Street which may have been renamed) and I really liked the gruesome name, so that is where the Music Hall in the story is located. There once was a theatre just across Fishergate from there, in Theatre Street.

When Alban, the narrator of ‘Livid’ leaves the theatre he catches a tram. Not far from my house is an unusual bus shelter. It too, has intermittently plagued my mind, prodding to be included in something creative. It has never been modernised and its frame appears to be either cast iron or steel. I read that its position and design are a consequence of its first function as a tram terminus.

About a mile from that is an atmospheric lane containing just a few large, impressive Victorian houses. It is not a cul-de-sac but it doesn’t go anywhere. It curves back to the main road to end only yards from where it starts. Walking along it always seems to take longer than it should; especially after dark. A property on that road became the basis of a house at the centre of my story.

The speech from the play, the tram shelter, and the Victorian house forged their triangle and Livid began to materialise. The tram shelter did not survive the crafting process but the tram did, subsequently conveying one of the most vivid passages of ‘Livid’. The distance between the terminus and the property helped the story structure, as did the necessary return journey. I can’t take any credit for that. All these components were embellished by the imagination in a way that is much more passive than authors like to imply. It’s strange, on reflection, how they all get tied together.

Beautifully grotesque

I’m thrilled to be included in the Modern Gothic anthology, alongside contributors from as far afield as the USA and the Philippines. All the stories are truly unique twists on Gothic standard styles. There are bleak religious tensions from the Appalachians, interminable chills as nature reclaims a home, a deeply disturbing rental contract, the crushing consequence of grandiose architectural ambition and a surge of the grotesque emerging – as it so often does in Gothic fiction – from behind the beautiful.

My story started with the performance of a play, though that began with a dream, or if I’m totally honest, with a nightmare. That particular kind of dream, it seems, is one that many others have experienced. I suspect that my son may have other nightmares, probably involving clingfilm and plaster.

Modern Gothic is available from discerning booksellers or directly from Fly on the Wall Press.

You can read the first 1000 words of Livid here: One of those dreams

Devilish footnote

Perhaps we drew down a curse by performing Undead. The same cast hit the headlines four months later, and caused an unholy storm. You can read about it here: The Transgender Mysteries.