Grasping the Gothic part five: Peake perfection; made in China

Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy is as Gothic as some people want to get. It stops short of the gore-fest craved by hard-core axe-and-chainsaw lovers, though it has its gruesome moments, and it avoids the phantom-infested intestinal crypts favoured by paranormal fantasists, but it is rich with grotesque characters, riddled with stacks of chambers and endless corridors, sinks to murky depths and soars to puncture and slash the storm-pregnant sky with its innumerable pinnacles. There is no such thing as pure Gothic, because the Gothic always requires some impurity, but the Titus Groan and Gormenghast novels are as purely impure as any traditionally grounded 'gloomth' (see:The Godfather of Gloomth) aficionado might desire.

Titus Groan, was well received but was not initially a financial success. Fortunately for Peake, he had plenty of outlets for his talents though the work was not always well-paid. In addition to the trilogy for which he is best known, he also published works of poetry, wrote plays and drew illustrations for classic works such as Alice in Wonderland, The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner, Treasure Island and The Hunting of the Snark.

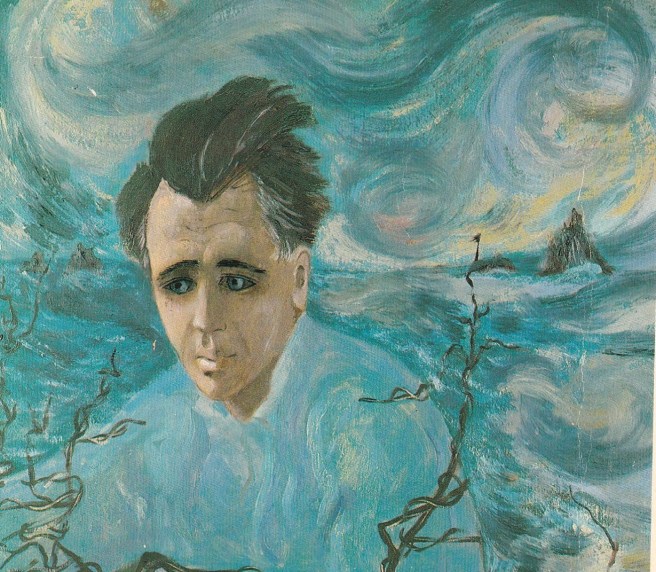

It was no surprise to learn that Peake was as much an artist and illustrator as he was an author. The books comprise a rich and intensely redolent prose, of a range and weave rarely found in contemporary literature. It was fortunate for us that he got into print before the modern dictum for fewer adjectives made effusive fiction an endangered species. The Gormenghast environment is not so much described as verbally painted. The characters are too well fleshed to be types, but in each case, their physicality and psychology are at once both instantly recognisable and yet entirely individual. As with the people in Peake’s drawings, we are presented with persons we have known but never met.

Whether sketched, as on the cover of Peake's notebook above, or described in words, there is a terrific visceral biology evident in each character. Some are almost invertebrate in aura, while fully human in physique. Their posture, motion and observed motivation is reminiscent of creatures that normally have a thorax, while others are, porcine, vulpine, feline or avian. They have lairs, dens. nests, roosts. A pair of twin sisters literally branch out.

The world in which the story is set is entirely contained within the books. It is never contextualised or explained. It is where it is. Gormenghast manifests as a city state. It is a magnificent castle, extending for miles, and holding jurisdiction over those living on its fringes. The members of the ruling family of the Earl of Groan are central to the story, but equal prominence is given to their servants, some of whom provide the painful schemes, blades and flames of the plot. It is a tale of ambition desired and destiny detested. It is a timeless allegory applying a spyglass to those who want power and those who crave to avoid it. Look here to find sympathy for the one whose life is determined by the womb in which they did not choose to be conceived. That’s all of us.

Fundamental to this epic is the absurd rule of tradition. Here institutionalised convention is taken way beyond the nth degree. Things are done according to great volumes of prescribed ritual, though the acts are clearly absurd and without benefit, except for the reassurance that they have been reenacted. That straightjacket of convention tightly holds the humour and the tragedy to the irregularly beating, slightly enlarged, heart of this chronicle of despair, hope, aspiration, and unrequited devotion. This is a tale infused with the core Gothic components of the grotesque, the ominous, the theatrical, the incessant and the chilling. Wrapped as it is, in layer upon layer of chamber, corridor, vault, tower, cellar and tailless serpentine pathways, the gloomth is tangible, inescapable and above all, architectural.

Whence did this come?

Mervyn Peake’s father was a British Congregational Missionary doctor serving in central southern China where, at Kuling in July 1911, Mervyn was born. A few months after his birth, the family relocated as Dr Peake took over the Mackenzie Memorial Hospital at Tientsin, a thousand miles to the north. John Watney writing in the introduction to Maeve Gilmore’s book Peake’s Progress tells us that ‘a box within a box, like a Chinese puzzle’ is a very apposite description of the Peking/Tientsin area at the time. Peking was a city within a city within a city, and that description helps to explain Mervyn’s imagined metropolis. The Chinese climate extremes that he experienced also informed his depiction of some of the weather events crucial to the plot of his masterpiece. His artist’s eye preyed on the cultural details he saw, such as the intricate carvings with which the Chinese merchants decorated their business premises. All the while, the Asian ambience was being infused with Anglophilic history and English literary standards as delivered in Tientsin Grammar School situated in the British concession of the city. His education was later completed in the United Kingdom at Eltham College in London and then at Croydon School of Art and the Royal Academy Schools.

While the Chinese influences explain the sheer scale of the Gormenghast architectural expanse and some of the detail and style of the constituent devices, the oriental far from dominates the mood and backdrop of the trilogy. It if it did so, it would be presumptuous to classify the work as Gothic. Those influences may have seeded some aspects but it is Peake’s mind that built this city, and his eye has been guided by his unique vision, seen through a scratched glass darkly but with botanical precision, biological observation and nightmare exaggeration. Gormenghast is as Gothic as you wish to imagine it.

It is surprising that there have not been more cinematic and television adaptations of this most visual of literary epics. There are few works more suitable for the big screen treatment of the kind bestowed on the masterpiece of Peake’s contemporary: Tolkien. The BBC adaptation (available on YouTube) contains many excellent performances by prominent actors of the time. It was broadcast in January 2000. Prime-time regulars give vent to supreme exaggeration entirely in keeping with the nuanced caricature evident in Peake’s writing and drawings. It is worth watching for the performances of Fiona Shaw, Zoe Wanamaker and Lynsey Baxter alone. Overall, however, a great fan of Gormenghast and I, find the scenes too warmly lit, and the scenic style not consistently gloomy enough to bring out the true mood of the books. It is more punk-baroque than Gothic. I strongly suggest that you read Titus Groan and Gormenghast before you watch. Imagine Peake’s dream for yourself, and let that be your lasting impression.

Peake is unique. There is no other writer or artist with his style. It is so refreshing to find a securely original perspective infused throughout with such a distinctly dark elegance. His signature tone reeks of life strained through a rusting sieve of inevitability. It is life that has gestated grotesquely to face the incessant ominous theatricality of destiny. It haunts and chills, but also amuses and entertains. There are laughs in there too. It’s good to laugh. While you still can.

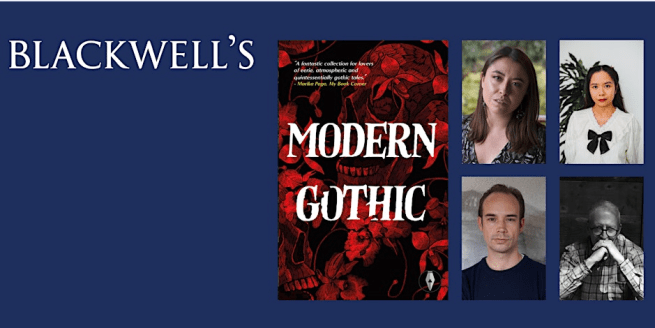

Ahead of the publication of Modern Gothic an eerie anthology from Fly on the Wall Press uneasywords is exploring the Gothic genre, its origins, influences and development.

It is now less than three months to publication on 11th October 2024. You can join me and three of my fellow gloomth-wranglers at Blackwell’s bookshop in Manchester on that day. We’ll be there after dark.

Get your tickets here: Modern Gothic Manchester Launch