Grasping the Gothic part one: emergence and petrification

Ahead of the publication of Modern Gothic an eerie anthology from Fly on the Wall Press, uneasywords is exploring the Gothic genre, its origins, influences and development.

Goths, and Goths, and Goths

Let’s exhume the genesis of the Gothic. Its precise beginnings are cloaked in the murky miasma of mid-European time. The Goths were significant thorns in the northern flanks of the Roman Empire and certainly contributed to its eventual downfall, but who were those people and where did they originate?

Some sources first find them in southern Scandinavia, others unearth them on the banks of the Vistula River in Poland, but questions haunt the accuracy of each of those assertions. The general consensus classifies them as a Germanic people (i.e. living in north-western and central Europe) who emerged during antiquity and remained as significant groups into the Middle Ages.

By the sixth century there were already two distinct tribes of Gothic people: the Visigoths, who after smashing the Romans at the Battle of Adrianople in 378, and ransacking Rome itself in 410, migrated as far as Spain; and the Ostrogoths who emerged a little later and ended up ruling areas of what is now northern Italy. The spread of Gothic dominance was initially viewed as the consequence of classic north-south punch-ups and subsequent southerners with an axe to grind cast the Goths as barbaric primitives, but more enlightened and less biased thinkers have come to see them instead as liberators with praiseworthy politics. The very earliest manifestation of western liberal governance can be traced to Gothic courts.

Our destination is a literary one, so we must concern ourselves with words. Why were the Goths called Goths? Well, it gets complicated because no one really knows. It is postulated that the word may be linked to the origins of other northern European words such as Gutes which refers to the people who lived on the island of Gotland (Sweden). It is also suggested that the word goth might have originally meant something like ‘pours’ referring perhaps to the nature of a river. (And now my heart chimes. The name of my local river, the Ribble, may have a similar origin with a word that meant ripping or tearing in a gushing sense.)

The term Gothic when used as a cultural label during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had a broader and often more derogatory implication originally than it does today. This is partly as a consequence of the role of the Goths in ancient history. Because their victories over Rome inevitably resulted in the destruction of classical buildings and monuments their own legacy is labelled as less sophisticated and crude. Hence even ancient megaliths that had no connection whatsoever with the Goths – Stonehenge for example – became labelled as ‘ancient Gothic’ due to their massive, heavy and coarse construction. Medieval buildings that were light and delicate by comparison were classified as Modern Gothic.

From blood to stone

So, Gothic takes us to central / northern Europe, but while the aesthetic genre of that name evokes some of the mistier ambience of the cooler seasons in those environs, it doesn’t really summon up the atmosphere of gladiator-biffing riverside dwellers. The first and lasting link between them and Horace Walpole, Bram Stoker, Charlotte Bronte, Charles Dickens, Jane Austen (yes – be patient, we’ll even visit her literary palette in future posts) and perhaps the ultimate maestro of the genre – Mervyn Peake – is carved in stone. We need to leap forward half a millennium.

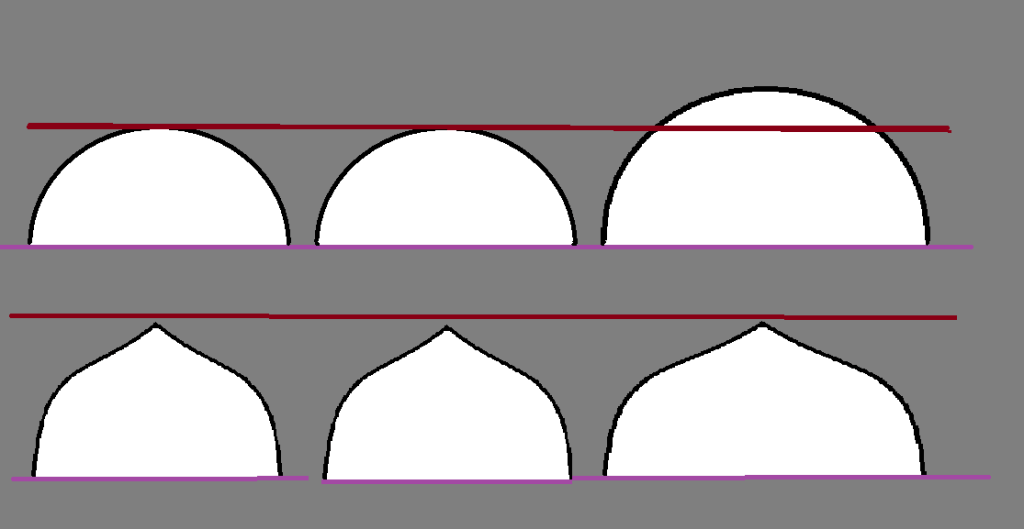

Gothic Architecture is the true stone-mother of the genre. It emerged in Europe from the twelfth century onwards. It is characterised principally by one striking feature: pointed arches. This apparently minor modification was revolutionary and it inspired and made possible several of the other constructed components that we associate with the style.

The point

Prior to the Gothic method, arches in churches, cathedrals, castles and cloisters were either rectangular or circular. The linear option has limitations determined by the weight and length of component parts. The circular may span more pleasingly but it poses problems with consistent height. Semi-circular arches can only be the same height if they are of consistent width. This is because the radius determines the height. That is fine if they are in a line, or surrounding a square space, but if they are required to frame a rectangle there are difficulties in achieving a pleasing aesthetic. The arches on the longer sides will have to be wider and hence taller. Either their peaks or their feet will be out of line in the vertical plane if the tops or the bases are to match. The pointed arch solves this problem at a stroke of a stone mason’s chalk. The point can be widened or narrowed and the peaks will all line up lovely.

The pointed arch also had symbolic doctrinal benefit in that it directed the penitent heavenwards and petrified the praying gesture. It visually echoed the church steeple. Windows were fashioned in the same shape to match the interior masonry and if you split the pointed arch and insert a nave in the gap you get a very useful pair of flying buttresses. The ‘flying’ is a misnomer as the buttresses are very firmly grounded and their purpose is to prevent the walls and roof from flying, or falling. So good were these buttresses that they allowed the walls between them to be less bulky giving rise to larger and taller windows and this evolved into what became known as ‘lantern’ churches because they were infused by so much light during the day and radiated so much if candle-lit at night.

Another consequence of the pointed innovation was that columns became more graceful and their flexibility meant that wonderfully vaulted ceilings emerged. Gradually more and more elaboration and decoration was added and Gothic metamorphosed into the over-rich style that now typifies that architectural milieu. That, in turn, would be further ramped up by the Gothic Revival movement – but that’s for another time. Let’s consider how classic Gothic became the literal background to later fiction.

Stone stories

The Gothic style of stone masonry was intended to evoke the more grandiose emotions. It is difficult to comprehend the true impact a finished Gothic cathedral must have had on medieval and early modern humans. Its size, scale, structure, and craftsmanship would be so far removed from their everyday experience that it must surely have felt like they were entering a portal to another world. In addition to the awe and wonder they could not help but be refocussed onto thoughts of higher and perpetual purpose, but as well as invoking hope, the decoration also reminded them of consequence. Not all the sacred adornment was benevolent. Fallen angels, devils, gargoyles, imps, and serpents slithered in. A great deal of Christian iconography is brutal, and served up with the added psychological acid of blame. The church-goer was not only responsible for their own suffering, but also for the torture of those who suffered on their behalf.

Vaulted ribs are truly beautiful, but there is something of the carcass about them. Even high-level corridors have a subterranean feel. Everything bears the imprint of so much movement, but is now so very, very still.

In addition to being awesome, Gothic architecture is also haunting by its very nature. It confines space with permeable boundaries. Arches both enclose and admit. Transepts can be only partially seen from the naves and vice versa. Screens and divisions and galleries and side chapels and altars and stone enclaves all obscure as well as reveal. Who knows what lurks in those high out-of-reach but not quite out-of-sight corners? And there are so many corners.

So, the Gothic gave birth to a new style of haunting, an aspect amplified by an architectural life after death. When Henry VIII lost control of his loins leading to his divorce from Catholicism his eventual revenge on the Papal institutions was pitiless. It wasn’t the only reason that Gothic went into decline but it was a significant one in England. We are fortunate that some of the greatest examples survived Henry’s harrowing but that, along with the subsequent religious persecution inflicted by the ruthless purges of the Reformation, put paid to many abbeys, monasteries, churches and the like. It was important to the reformers to rid the land not only of Roman doctrine but of all the trappings of excess attached to it. Hence the emblems and icons of popery had to be removed and destroyed. Functioning Gothic is spooky enough; ruined Gothic haunts to a whole new level.

When ruined, Gothic embellishment became associated with evil and that which once had been sacred became diabolical. It was enough to alarm the peacefully sleeping. The dead refused to lie down.

The raison d’etre of a Christian church is to persistently remind the living of the dead; not only those who have gone before, but also those who lie ahead – most appositely, the worshippers themselves. Living your best life, they say, might just result in your worst afterlife.

The churchyards outside are carpeted by the departed, the vaults, tombs and memorials within embrace the living penitents with the accolades, pleas and bones of those who have gone but are not far away. We associate ghosts with graves in much the same way that we link birds with nests, but this is faulty logic. You are much more likely to see a bird when it is nowhere near its nest. Nevertheless, churches, by their very presence, petrify mortality. This is an intrinsically Gothic theme. Gothic grotesquely reaches from the past to tap us on the shoulder and point towards an unavoidable yet uncertain future.

Gothic architecture became the backdrop to the earliest Gothic fiction and hence the ominous gloom and grotesque embellishments associated with that style of building, especially in its ruined state, were grafted onto the aesthetic rootstock of the genre.

It is a source of dark delight to find that the built environment is at the rotten core of several of the stories in the forthcoming Modern Gothic anthology. Buildings split with unnatural forces, are riddled with rampant rot, and rented by the settling of deeply unsettling contracts. Michael Bird’s monumental opener, A Glass House for Esther, admits us to this contorted collection, and Lerah Mae Barcenilla’s The City Where One Finds The Lost lusciously entraps us in its dead end. In those places and others in between, expect many sharp corners.

3 thoughts on “Sharpening the curve”