23 August 1944

During the summer months I do a good deal of my writing in my shed sitting at one of the large picture windows that face towards the east. Intermittently, aircraft approaching the main runway at the BAE airfield at Warton some seven miles behind me, fly directly into my line of sight and pass over the 1/72 scale Airfix model of a B-24 Liberator bomber displayed nostalgically under the apex of my shed roof.

By coincidence, when sitting at my desk, I am also looking directly towards my childhood home in the suburb of Deepdale, close to the soccer stadium of Preston North End. My bedroom there sported some 72 examples of 1/72 Airfix models. In my aircraft-mad youth, I would look up and see the Lightnings, Jaguars, Hawks, and Tornados of the 1960s and 70s on the same approach line to Warton. My father told me that he used to watch the Lancaster bombers on their descent during the Second World War. I think he was mistaken.

At that time the airfield was being used to receive and fit out American aircraft. Known as Base Air Depot 2, it employed over ten thousand people – mostly American servicemen – and processed over ten thousand aircraft, 2894 of which were B-24 Liberator bombers. To the untrained eye a Liberator looks very similar to a Lancaster. They were roughly the same size, with four engines, twin tail fins and gun turrets in similar locations.

I don’t think my father was watching Lancasters, I think he was seeing Liberators. He may have seen Liberator 42-50291, nicknamed ‘Classy Chassis’. He may even have seen her climbing away after her last take off, but he wouldn’t have seen her make her last ever final approach, because that day she descended from the west, not the east. She failed to land and in doing so killed thirty-eight children, two teachers, seven other British civilians, four RAF sergeants and ten USAAF personnel, including the three crew on board the aircraft.

What happened

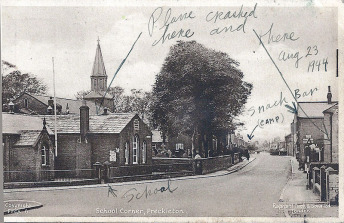

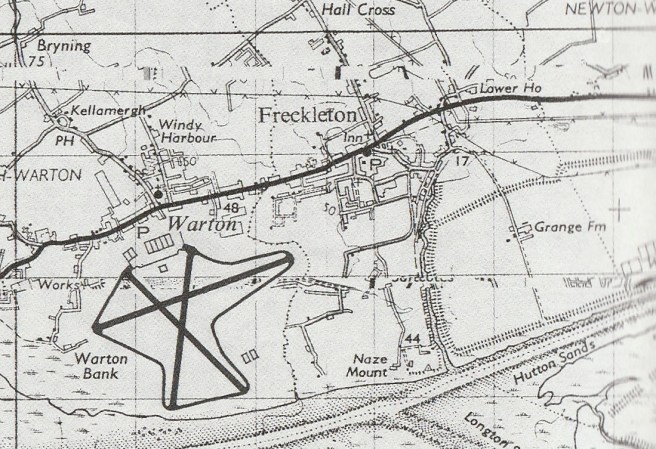

It was the morning of 23rd August 1944. The weather was fine with some broken cloud. Showers were forecast. At 1030 hours Warton’s control tower, received a priority telephone call from Burtonwood airfield, some twenty-five miles to the south, to inform them that a violent and fast-moving storm had passed and was moving in the direction of the Fylde coast. The two B-24 Liberator bombers undertaking local test-flights were recalled. Fifteen minutes later one of the aircraft crashed on the village of Freckleton demolishing half of the Holy Trinity School and destroying the Sad Sack snack bar across the road.

The cause of the accident is unknown but the testimony of the pilot of the second aircraft offers a vivid insight.[1]

First Lieutenant Peter Manaserro reported that conditions at take-off were favourable with a visibility of several miles and a broken cloud ceiling of over 1500 feet. He saw what he thought were scattered showers and some flashes of lightning in the distance. They headed north and flew at 1500 feet.

The pilot of the first aircraft, First Lieutenant John Bloemendal, contacted Manaserro to draw his attention to ‘a very impressive cloud formation to the south-south-east that looked like a thunderhead’. Shortly after that the control tower ordered them both to land because of the approaching weather. Manaserro reports following Bloemental in order to land as number two. About four miles out from the field they encountered rain. By this time they were at five hundred feet.

On the base leg (a flight path at right angles to the centreline of the runway) they both lowered their landing gear and shortly after that Manaserro lost sight of the aircraft ahead due to the worsening weather. He reported:

‘I was watching the ground as there was no visibility ahead. As I flew over Lytham I started a left turn to start the approach.’

At that point, Manaserro heard Bloemandal tell the control tower that he was pulling up his wheels and going round again. Manaserro said:

‘I could not see the ground and had to fly on instruments. I called Lieutenant Bloemandal and told him that we had better head north to get out of the storm. He answered “OK”. I told him I would take a heading on 330 degrees. He said “Roger”. That was the last I heard from Lieutenant Bloemandal.’

Classy Chassis hit the ground at approximately 10:45. The school took the worst of the impact before the wreck of the plane slid across the road and ploughed into the Sad Sack coffee bar. Warton’s fire department was at the scene of the crash within minutes. Some children were freed from the debris and taken to Warton’s hospital. Unfortunately the majority were beyond help and were taken to a temporary mortuary for identification. The final casualty to lose their life was Maureen Clark who died on September 4th. By then the majority had been laid to rest following a mass funeral on August 26th, just three days after the crash.

The blame

The investigation board eventually published an opinion that the crash resulted from the pilot’s error of judgement of the violence of the storm. They may be right, but that is one hell of a weight to posthumously lay on one person’s shoulders.

This was at the peak of the war. The invasion of Normandy had only occurred some two months earlier. There was immense pressure on the base at Warton to process the aircraft and get them into frontline service, so the testing schedule was interminable. It became necessary to test fly over eight hundred aircraft in a month. Some days were lost to bad weather and hence sometimes as many as fifty aircraft were test flown in a single day. [2] Bloemendal, who was an experienced pilot, would be used to flying in a variety of conditions, but weather forecasting and reporting was a shadow of what we know today. Apart from the visual observations they had made after take-off, the only information he had was the instruction to return to base, and that in turn was drawn from a single telephone call from the airfield at Burtonwood. His final radio communication demonstrates that he had decided that it was not safe to attempt a landing, was retracting the aircraft’s undercarriage and was ‘going round again’. Was that really an ‘error of judgement’? According to Manaserro, that call preceded his own decision to abandon the approach and head out of the storm.

What caused the crash?

One witness reported that the fateful aircraft had been struck by lightning which broke the Liberator in two. There are a number of problems with this. Lightning strikes to aircraft in the air do not usually cause structural damage because the airframe acts as a Faraday Cage conducting the current around the fuselage. Also, other witnesses on the ground reported that the rain was so heavy that they could not even see across the road. It is unlikely then, that someone could see the aircraft with any clarity. It is more likely that they saw lightning strikes that did not hit the plane, or perhaps they saw flashes or sparks generated by the impact with the school which may have illuminated what was an aircraft fracturing as a consequence of the crash.

The accident investigation also postulated that the aircraft may have experienced structural failure due to the violence of the storm. This too, is highly unlikely, though it is not at all impossible that the very strong turbulence within the storm may have caused ‘Classy Chassis’ to roll, yaw or pitch suddenly and with a severity that the pilot could not correct. The hypothesis that the plane experienced a sudden overwhelming downdraught pushing it into the ground is feasible, but in common with all other suggestions, lies beyond the possibility of proof. Wartime aircraft did not have ‘black boxes’ and the wreckage was so extensive that it was impossible to establish what state the Liberator had been in before she hit the school.

There is one important observation that appears to have been largely ignored at the time, but which adds possible clarity. It appears that the B-24 made contact with a tree prior to hitting anything else. That would have been sufficient to tip it out of kilter so strongly that the tragedy then became inevitable. (Whilst I was compiling this post, it was reported that two Greek aircrew died after their plane clipped a tree and crashed while fighting wildfires on the Greek island of Evia. Video footage shows that little damage was caused by the tree, but the pilot was not able to recover sufficient control to avoid the crash.) But why was ‘Classy Chassy’ so close to the village?

The geography

As can be seen in the map illustration, the village of Freckleton lies north of the centre line of runway 08/26. How then did Classy Chassis collide with it? With visibility so poor, Lieutenant Bloemandal may have had difficulty in seeing the runway (a possible reason for him ‘going round’ again), so the B-24 may not have been aligned with it. Alternatively, strong and sudden wind variations may have blown the aircraft off course.

Runway 08 is the one running west-east from Warton Bank.

It is possible that Bloemandal may have started his circuit to make another approach. (In this context a ‘circuit’ is a rectangular flight path with the runway being the centre section of one of the long sides of the rectangle.) Manaserro’s account confirms that a left-hand circuit was in operation i.e.: a flight path with four left turns. Normally the pilot would ensure he was clear of the village, or had sufficient height to fly safely over it, before executing such a manoeuvre. It is unlikely that Bloemandal could clearly see the village and his altimeter may have been inaccurate, as will be postulated below.

Another possibility resulting in his fateful location may have resulted from his final broadcast. Bloemandal’s last words were to acknowledge Manassero’s suggestion that they both turn towards north to fly out of the storm. He may have commenced that manoeuvre. The same restrictions compromising the data available to him would apply. He may have thought the aircraft was higher than it actually was, especially considering that he had not touched down on the runway.

All of this is speculation, but one or more of these explanations placed the plane over the village, whereas a flight path extending from the centre line of the runway would have taken it over the agricultural space to the south.

So much for the latitude, but what about the altitude? Why was the aircraft so low?

The height

It is almost certain that Lieutenant Bloemandal would have pushed forward the throttles and pulled up the nose of the B-24 before he radioed his decision to ‘go round’. These two changes would have boosted the thrust of the engines and increased the lift of the wings and therefore should have curtailed the descent and commenced a climb. There was sufficient time for a further broadcast conversation with Manassero before the fatal contact was made with objects on the ground during which he should have gained height. So why was he so low?

He may have been reluctant to climb steeply as a consequence of the cloud base being down to an estimated four hundred feet by this point. Climbing into the cloud would not improve visibility.

There may well have been a complete lack of reliable references. In essence he may have been flying blind. The basic flying instruments would tell him his altitude, speed and orientation. (NB above, that Manaserro reports flying on instruments as he could not see the ground.) The abysmal visibility is the most probable reason why Bloemandal aborted the landing. (It could also have been due to the treacherous conditions profoundly affecting the handling characteristics of the aircraft.) The two most important instruments – the altimeter and the airspeed indicator – were, in the 1940s, entirely pressure-based. Storms can contain significant pressure variations.

The royal Air Force Air Navigation handbook of June 1944 explains in plain English that:

“An altimeter is an aneroid barometer calibrated in terms of height in feet instead of in units of pressure.”[3]

Lieutenant Bloemandal would have set the barometric pressure at ground level at Warton on his altimeter prior to take off. He may have been advised of any changes from the control tower when he was recalled, but if the storm brought other significant fluctuations he would not have known. A drop in pressure would result in his altimeter indicating he was higher than his actual altitude. This may have convinced him he was at a safe height to make a turn. He may have had no real-world references to influence his decision. Anyone who has driven into a downpour at forty or fifty miles per hour will be able to imagine the visibility problem. He would be flying at more than twice that speed.

The possibility that the Liberator fell victim to a severe down-draught is believable. Such things do occur. Frequent flyers will probably have encountered turbulence. At 35000 feet it’s inconvenient, at 300 feet it can be fatal.

The most likely cause, to my mind, is a combination of two or more of the possibilities above, with the lack of visibility and the storm turbulence being the most probable.

Could it have been avoided?

It is vital to reiterate that avoiding crashing was precisely what Lieutenant Bloemandal was attempting to do. It is too easy to blame him for entering the storm, he had no knowledge of its severity and he had been ordered to land. In both attempting to land, and in aborting the landing, he was following designated procedure.

The only people with true knowledge of the severity of the storm were those who had experienced it, for example, the staff of the Burtonwood base. Quite rightly they warned their colleagues at Warton. Did they stress the severity sufficiently? Did they also emphasise the limited duration of the downpour? Was all this properly digested and processed at Warton?

With the benefit of hindsight, it would have been better to tell the pilots to skirt around the storm – a decision that Manassero made for himself and successfully accomplished. Alternatively, they could have been diverted to other bases. During the war there were fourteen airfields within a thirty-mile radius of Warton and at least three would have easily accommodated the B24: Squires Gate (Blackpool), Salmesbury to the east and, of course, Burtonwood to the south, where we know for certain that the storm had passed.

The responsibility

The term ‘act of God’, meaning an event beyond prevention by humans, is rarely used these days, but ‘act of nature’ could surely take its place. The Freckleton Air Disaster, to my mind, was an act of nature. It was atmospheric forces that brought about the crash, but that is not to eliminate an element of blame. There were deliberate decisions taken and deliberate actions applied that killed the adults and children of that village, but they did not take place in or above Lancashire, but rather some years earlier and a thousand kilometres to the east: in Berlin.

Were it not for the war, ‘Classy Chassis’ would not have been in Lancashire, Lieutenant Bloemandal would not have been flying over Warton, and the base itself – built between 1940 and 1942 – would not have been there. Those killed by the crash at Freckleton on 23rd August 1944 were not the casualties of an accident; in common with millions of others, they were slain in the name of nationalist aggression.

The Legacy

There is a war memorial in the heart of the village for all who died in service of their country. A section of the churchyard is dedicated to the victims of this specific disaster.

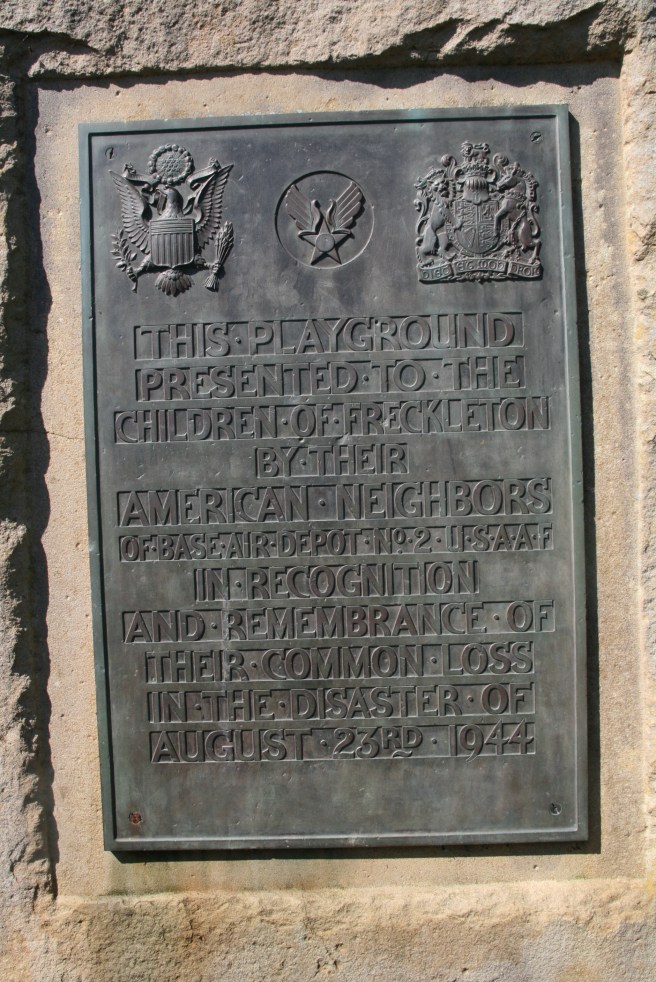

The personnel of BAD2 donated funds to create a lasting memorial to the victims. A playground was created and handed over to the village.

Notes and references

After the war ended, Warton became an RAF base and then entered private ownership. The airfield is now operated by BAE Systems. The main runway is longer today than it was in 1944 and has been renumbered 07/25.

Footnotes

[1] See: Holmes H, The World’s Greatest Air Depot, Airlife Publishing 1994, page 77

[2] Ibid, page 53

[3] Air Ministry, H.M Stationery Office. 1944 page 25

Other information from: Ferguson A.P., Lancashire Airfields in the Second World War, Countryside Books, 2004.

Influenced

In 2013 I made a proposal for an open-air performance commemorating the disaster, to be held as part of an Arts festival in nearby Lytham St Annes. It was declined by the organisers on the grounds of local sensitivities still being too raw, though I suspect my inadequacy at justifying the nature and costs of the project may have also been a factor in the failure of the submission.

The play was never written, but the concept became a short story published by the Lancashire Evening Post n July 2017. The story can be found in The Atheist’s Prayer Book .