The remaking of patterns

The familiar question came again.

“Where do you get all your ideas?”

The answer is unchanged.

“From the same place as you.”

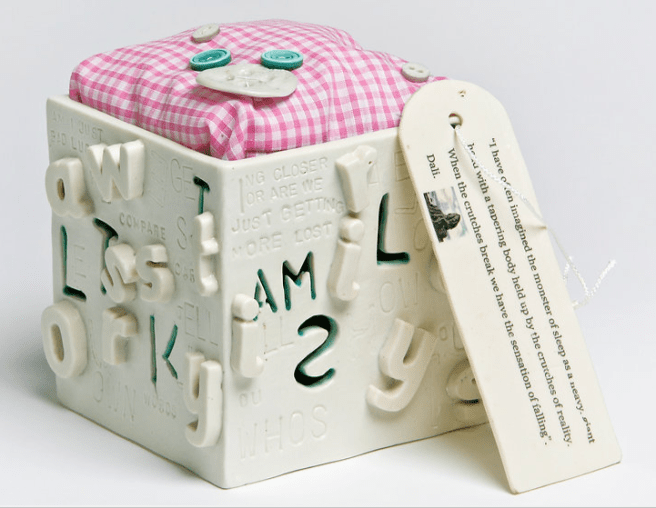

Yet she was a ceramicist and I a scribbler. Judging by the display on her stall she is every bit as creative and productive as I, if not more so. We both work with patterns. I compile black and white designs on virtual paper, she crafts with form, colour, size, shape, gravity, balance, structure and function in the physically tactile world. She re-shapes the earth itself and bakes it into fragile permanence. She is much more dexterous than I. Ceramicists are more skilled than scribblers, yet few people aspire to add ‘ceramicist’ to their self-attribution.

There is nothing superior about compiling words. I have written before why I am entirely comfortable setting out my bookstall at craft fairs.[1] I feel at home among fellow artisans, and they, without exception, have welcomed me. It’s all about pattern.

There are two layers of pattern in storytelling. There is the visual or audible shape of words on paper, pixels on screen, or sounds in the air. They trigger a second visualisation in the mind of the reader or listener. The first layer is the only one the scribbler can control. The second design is unique to the person who receives the first. No two receivers will make the same imaginary realisation, and the scribbler will never know the appearance of what they have caused to be created.

The same is true for the ceramicist. The pot is fired and put on display but the crafter cannot imagine the secondary shape: the association that the viewer or handler conjures from the pottery.

The ceramicist sometimes includes words, but hers are three dimensional, mine have only two. Hers are formed from the Earth’s own ancient alphabet. They are elementally regenerated.

Writers are sculptors too. All creatives are. We see patterns in the world and rework them. We pass on our recycled patterns and those who accept our donation do likewise and make gifts to themselves.

All animals survive by recognising patterns and noticing when they change. Whether they be visible, audible, olfactory or tactile, we are reassured by the consistent and alerted by the different. The change can be pleasurable or fearful.

The scribbler’s pattern manipulation is dependent upon the genre of the story. Sometimes we start by breaking the patterns of a character’s behaviour or see how they are damaged by serendipity. Alternatively, we begin by disrupting the imagined environment.

The dystopian world is one in which the background is the major disruption. The reader is perplexed, wondering if normality can be restored. Imagine a world in which all we take for granted has been taken away. Could you cope?

Historical fiction provides a similar problem to the reader, the rupture is probably less extreme and maybe more convincing, because we know that our forebears faced the equivalent reality. Some things are the same, but others are missing. Our ancestors did not have the knowledge, understanding and technology that we find so helpful. They navigated their way. Could you have done so?

When the fiction is set in living memory the creative challenges are delicate. Accuracy and detail are crucial. Shuffle the pieces too much and the credibility crumbles. The story-fusing crucible cracks in the creative kiln and spoils the finish. Research is simpler though, so the pattern-maker has more to draw on. Here it is the surface decoration that requires scrupulous attention to detail, for what really fascinates the reader are the shuffled shapes of minds and hearts.

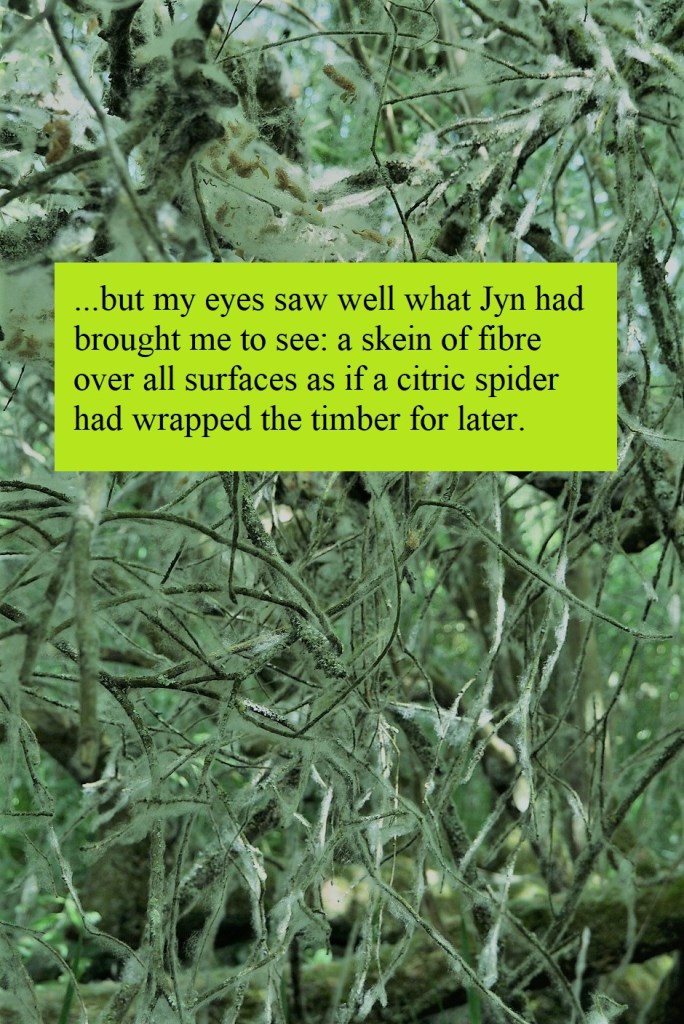

If the background is more or less intact it is the microscopic that needs the closes scrutiny. The patterns that we cannot see could be the ones we need to watch.

The writer’s choice of narrative clay is crucial to the shape of the story. The ceramicist asserted that porcelain is particularly precious because of its consistency and pliability. Porcelain has memory she declared. The scribbler made a mental note of that.

The porcelain is made with memories; no wonder it can make more.

Both scribbler and ceramicist have seen patterns, reformed them into novel arrangements and offered them to others. As authors we are constrained by our limited supply of stock shapes. We simply change the order of the typographical characters in the language. Ceramicists have more fluid constituents. They work in more dimensions; they manipulate the very substance of the artwork.

They seldom stop to think, I suspect, what the owner makes of the pattern they have supplied beyond the joy of the aesthetic appreciation. They surely cannot imagine the subsequent imaginary adventures that the custodian can add.

So the scribbler and the ceramicist, side by side at the makers’ market are but different species of the same genus.

If you work with clay, wood, metal, wax, paint, fabric, flowers, or any other physical substance you may marvel at the abstraction in my written work, but please hear that I am in awe of the dreams you may liberate.

I know where you get all your ideas, but if I found them first, I could never reshape them the way you do.

Who knows what stories you have started?

References:

Links:

Please check out Philippa Whiteside’s website and Facebook page.

Click on the book pics below for more about each of them.