Goodbye Modern Gothic year, it was good clambering through you. The culmination was the launch tour, with two sessions in Manchester, one each in Liverpool and Birmingham and one online. I found the experience fascinating.

Isabelle Kenyon (Fly on the Wall Press) Lerah Mae Barcenilla, Pete Hartley, Lauren Archer, Michael Bird

The launches themselves went well (as did subsequent book sales) and all the audiences were genuinely appreciative, but were they really there for the readings and if so, did the readings do justice to the stories? After a lifetime of producing theatre, it was rejuvenating, but also a tad unsettling, to get back in front of an audience for the first time for several years. While in transit between venues there was ample time to reflect on the purpose of that kind of event, and of the efficacy of reading in public. I formed the opinion that it is not as effective as it could be. Perhaps with just a tweak or two, public readings might be of greater service to potential readers, and purveyors of printed fiction.

Historically you do not have to probe very far to find accounts of hugely popular public readings of fiction. Dickens was renowned for them and benefitted considerably from sell-out tours – but was the demand for tickets driven by the desire to hear the story or to see Mr. Dickens? The latter, primarily, I’d wager.

Times have moved on. We live in a multi-visual world when it comes to entertainment. Perhaps it’s just me, but public readings fall short of doing it for oneself. I do not even like drama performances with books in hand. These are sometimes called rehearsed readings. They are mercifully rare. As a teacher of drama, I was notoriously intolerant of rehearsals with scripts in hand, insisting that lines were learned in advance of each rehearsal. In real life we do not go around speaking and moving in accordance with a script. This points towards what I regard as the nub of the public reading problem: it is a process that tries to turn literature into drama. They are, in fact, entirely unrelated genre. Yes, entirely.

Academics may wish to take me to task, but the distinction is clear. Drama is tens of thousands of years older than literature. It preceded all modern languages and may even have started when spoken vocabulary was in its infancy, but the key difference between it and literature is much more fundamental. With literature there is a direct line from author to page to reader; whereas drama, if it is written down at all, is written for the performer, who then rewrites the work – in multiple dimensions - for the stage. Theatre is perceived in precisely the same way the world is. Literature is entirely encoded in ciphers that must be known to be interpreted. When a written work is read aloud, the ears are hearing fiction while everything else in the room is signalling the fact of the here and now. When you perform drama almost everything in the performance space is working with you, whereas during a public reading almost everything else in the environment is working against you.

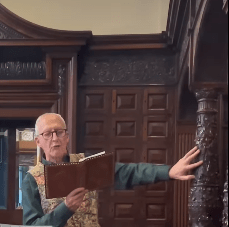

It was with this in mind, that upon discussing the promotion of Modern Gothic I promised that I would do what I called an enhanced reading. This involved learning sections of the reading so that they could be embodied and delivered as might a rehearsed monologue. Fortunately, the first-person narration lent itself to this interpretation. Third-person narratives are more difficult to present in this manner. This delivery went down well based on the feedback from members of the public.

Opting for that kind of presentation was not just a question of wishing to make the event more dramatic. Despite my background in theatre and teaching, I am not an especially accomplished sight reader. Learning parts of the text helped to smooth out most of my difficulties, though my main motivation was to improve the audience experience.

I tend to avoid events in which book readings are the focus. They simply don’t work for me. I’m too easily distracted by the background, the ambient sounds, and by interpreting the body language of the reader, which is often at odds with the content being described. Perhaps authors, publishers and booksellers might wish to reflect on this? Those kinds of events are integral to some marketing strategies. So how could they be improved?

Some suggestions

The venue

If the location matches the setting of the story, so much the better. When the eyes wander, they will at least be veering in the right direction.

The background

If the appearance of the venue is not in harmony with the fiction, it is far better to reduce it to something simple. A plain backdrop is preferable to one that is too busy or that bears references to distractions. Low-key neutral decoration, or a simple backdrop in harmony with the setting or mood of the story can really help. Even tastefully arranged potted foliage is better than the ordered detritus of the spines of alternative reading and posters for conflicting works.

The lighting

Another way of reducing the distractions is by judicious use of lighting. Focused lighting is available at a fraction of the cost it used to be. This can be used to diminish the visual impact of the surroundings and thereby distance the reader from the ambient and thus enhance the atmosphere of the fiction.

Unplug

Do you really need amplification? Microphones seem the default option these days, but for modest audiences in small spaces they are often completely unnecessary. They fix the sound source away from the reader and actually reduce the degree to which the reader can apply variation. They are yet again another reminder that the fiction isn’t among us. The risk is clear. Thanks to the continued persecution of genuinely useful skill subjects (like Drama) in schools, fewer and fewer people learn to speak in public, so maybe…

Use professional performers

Pay a person (or persons) to do the reading. Maybe they could do enhanced readings, where every word is delivered but not all of them are being read?

Edit the text

What? Sacrilege! Not at all. When I read from my Modern Gothic story, Livid, I actually used an edited version. I would never write as comprehensively for an actor as I would for a reader. This underlines another difference between drama and literature. Drama requires far fewer words because of the contribution of the performer. I also felt that some sentences that worked on the page, were inhibiting the best flow of stimulus on the stage, so they were omitted. You are not misleading the audience by making cuts. The point of a public reading is surely to promote the work by quoting from it – otherwise you should deliver the entire work. A public reading is a trailer, not the main feature. Hit them with highlights. While we’re on that subject: let’s keep the extracts brief. Two short readings may be more impactful than one long one and there is a reduced chance of inducing the dreaded destroyer: boredom.

It’s not me, it’s for you

My aversion to public readings is probably a symptom of a broader malaise, and this too, I suspect, may be shared by other readers and buyers of books. The audiences at the Modern Gothic launches were modest in numbers but interested and appreciative. It was clear that perhaps half of those there had been drawn by the subject matter. The other contingent came because they knew one of the authors or organisers. This is always the case, even when highly popular events draw sell-out crowds. The public feel they ‘know’ the author even though they do not. They may know of them, and they may be familiar with their work, but they do not know them. Theatre and cinema are marketed on the same basis, but in those arts the nature of the ‘star’ is integral. In the best fiction, it should be irrelevant.

Obscure the author

Public readings are often a promotion of the author not the fiction. Speaking as a reader; this is wrong. You are trying to sell me something I do not wish to buy. I have no interest in authors. I read a great deal and write even more, but in both cases, it is the content of the work that interests me, not who wrote it or why it was written, or whether they have written anything else, or been previously published or accoladed. All of that is irrelevant. It guarantees nothing. Is the work to my taste? That’s what I want to know.

Unless the work is a biography, the more invisible the author, the better the work. If I am thinking about the writer while I am reading fiction, it is not a great work.

Writers are often asked if they have favourite authors. I do not. I do have two favourite books: The Bell (Iris Murdock) and The Owl Service (Alan Garner). In each case I first purchased the book as a consequence of their serialisation on television. I knew nothing about the authors. It was the stories that seduced me. I do not need to know about the author in order to buy a book; I want to know about the content.

The Last Grasp

I hope that during the promotion of Modern Gothic, I helped potential readers to sample the stories within. I was keen to do more in that respect, but time was limited. I was pleased by the humility of my compatriots, who were mutually supportive and kept their focus on the work we had compiled. I felt we could have more fully championed the work of the contributors who could not be among us, and I do encourage you to immerse your imagination in the entrails of theirs.

You can find out more by sifting through some of my previous posts, or by simply grasping a copy of Modern Gothic.

So, the Gothic year is gone. New adventures await. If they are good enough, I’ll tell you all about them.

One thought on “Reading without the room”