Lecture notes from ‘Gloomth and the Six Pillars of Gothic’

House of Books and Friends, Manchester, in association with Fly on the Wall Press

29 October 2024

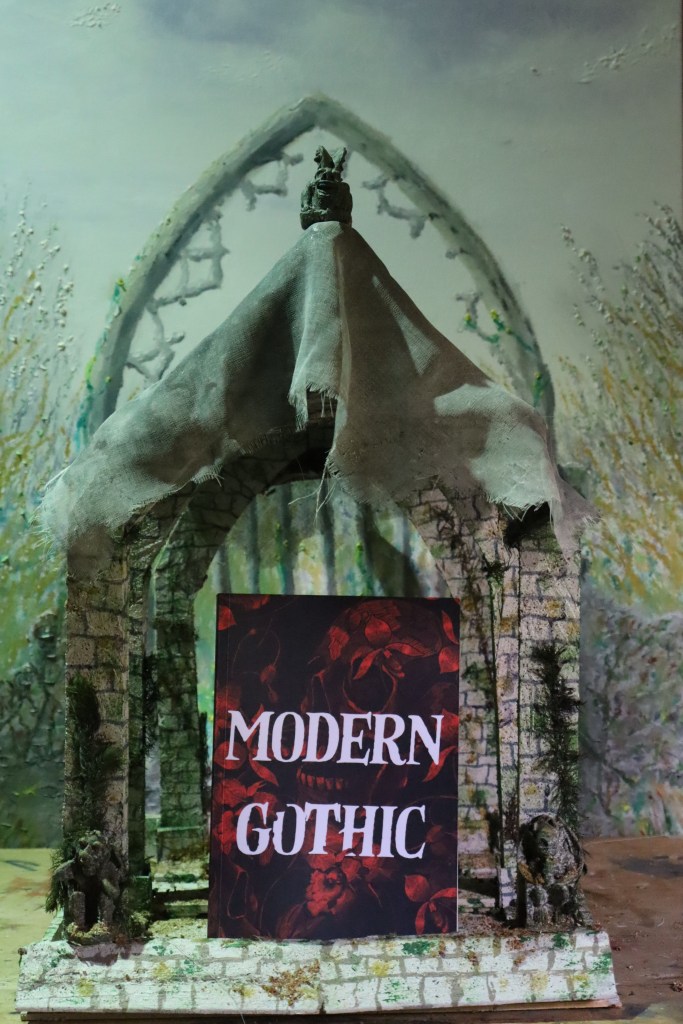

This lecture was constructed around seven short extracts from Modern Gothic. Those extracts are referred to and outlined, but not quoted in full here. The book is now widely available.

I began with the most dangerous three words a speaker can start with:

Go to sleep my babies

David Cousins. Ghosts

Don’t you wake up

The stars will keep you company

So close your eyes

Old Uncle Moon will smile his dearest sweetest dreams

And hold you in your arms

Until the morning comes.

Dark the night, not a sound

Damp and cold, frosty ground

Above your head the lion screams

To tear you from your moonlit dreams.

Damp with sweat, mouth is dry

Twisted branches catch the eye

Beside your bed the angel stands

You cannot touch his withered hands.

Tell me children

Are you sleeping?

Are you innocent, like me?

May you never cross the line

I hope your dreams

Are not like mine.

It probably seemed self-indulgent for me to start my talk on the Gothic genre with a quote from an album track by my favourite band written by my favourite songwriter, but there are multiple justifications. Dave Cousins is my favourite writer full stop. Had I not spent far too many teenage hours supine on the sofa intravenously imbibing (via a needle) his lyrics, it is unlikely that I would ever have put my own pen to paper creatively. He describes the music of the band as “Gothic rock” and the Strawbs really do lead us directly to the origin of the literary genre.

Strawbs are called Strawbs because they used to rehearse in Strawberry Hill, West London, and Strawberry Hill is so-called because of Strawberry Hill House created in the eighteenth century by Horace Walpole, writer of the first ever Gothic novel and provoker of the Gothic Revival movement in architecture.

Everything about Strawberry Hill is fake. It is all pretend Gothic, built to satisfy the fantastic tastes of its creator. It contained one of the earliest private printing presses and was where Horace Walpole wrote a great many works including The Castle of Otranto which is regarded as the first ever Gothic novel, though from a modern perspective it is less of a spooky story and more of a mediaeval fantasy romp. To Walpole, all things northern and mediaeval were Gothic. (See my earlier post: The Godfather of Gloomth]

In my opinion Gothic Revival architecture is more Gothic than original Gothic. It is more elaborate, more cavernous, more intestinal, more labyrinthine. To fully appreciate the atmosphere created by Walpole’s fabrication you really have to imagine it by candlelight. It was during the creation of his “toy house” that Walpole coined the term “gloomth” to describe his desired ambience.

The built environment in general, and Gothic architecture in particular, became an important backdrop to early Gothic fiction. (You only need consider the titles of some of the most famous works, The Fall of the House of Usher, Wuthering Heights, Gormenghast etc.) The stage director Peter Brook said that “the set was the geometry of the eventual play” meaning that whatever construction was made on the stage would determine how and where the actors, and hence their characters, would move. This is also true in literary fiction, to the extent that in some fiction the architecture is so influential it becomes another character. The built environment features in all six of the Modern Gothic stories and in at least four, either its physical existence or matters of ownership, leasing and maintenance, are integral sinews of the plot.

Michael Bird gets us underway in that very typical Gothic tradition of using built structures to enclose, but he also provides us with an excellent early example of what I believe to be an absolutely fundamental Gothic component, and the first of our six pillars.

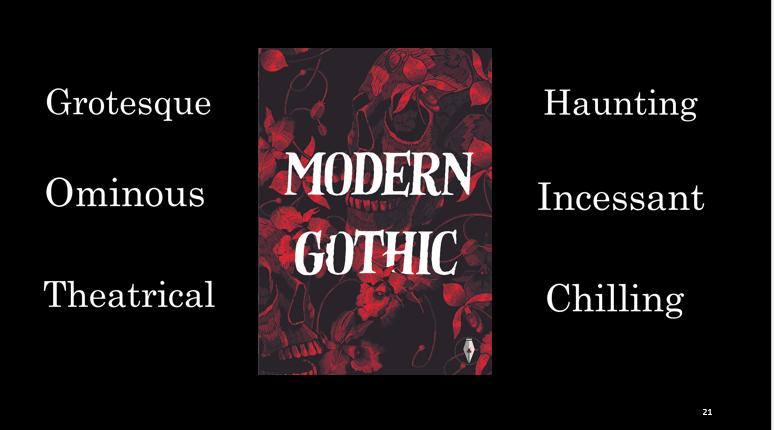

In A Glass House for Esther, the eponymous only child of a very wealthy Herbert Cardew is indulged and enchanted by the filling of a huge conservatory – a square mile of glass and iron – with exotic flora and fauna. All is enchanting to begin with, then things do not go quite so well. One of the finest examples of our Gothic genre pillar begins with the delivery of an especially beautiful creature on page 10. The outcome of this delivery is not at all beautiful. In fact, it is horrible. This particular punch is over by the foot of page 11, but the damage is done, the agenda is set. This, I believe to be a cornerstone of Gothic fiction. The gorgeous gives way to the grotesque.

The repulsive image in a Gothic story is frequently found among the beautiful, or emerges from behind the banal, or is a transformation from the attractive into the repellent. Consider, for example, the first classic gape of a handsome vampire. Another example is Miss Havisham from Dickens’ Great Expectations (pictured in David Lean’s movie above) surely one of the most grotesquely damaged of all of Dickens' characters.

Once we have glimpsed this kind of jolt, we have already caught sight of our second pillar…

No one does ominous more seductively in Modern Gothic than Rose Biggin. Her A Respectable Tenancy is a paragon of the intensifying anticipation of the terrible. The apparently benign remark on page 92 that there is a peculiar rental situation is the first hint of something that will be as compelling as it is repulsive. This is classic Gothic. We want out, but nowhere near as much as we want to find out. We’re hooked. And hooks can hurt. We know that. To get the full delicate delivery and delightful context read the whole of pages 91 and 92.

Titus Groan (pictured above in the BBC adaptation of Gormenghast) provides such a hook in the first book of Mervyn Peake’s magnificent trilogy as soon as he is born.

“What is the matter with my son’s eyes?” asks Lord Groan.

Doctor Prunesquallor replies: “They are violet.”

Oh dear, we think. That doesn’t bode well. Once the ominous is in place things thicken and the third pillar begins to emerge:

You might think I will use my own story here, but all Gothic fiction has a theatricality to it, and all six stories in the anthology exhibit this. What I mean by ‘theatrical’ is that the story would sit well on the stage and/or screen and if the Gothic genre has proved anything it as proved that. (If you want a blatant example of modern Gothic – watch a Meat Loaf video.)

In the theatre everything has to be at least a little exaggerated. Characters in Gothic fiction behave this way as a consequence of the external, often supernatural, influences that they perceive. If you read pages 67 and 68 of Modern Gothic you will see those pressures coming into play as Ed Karshner’s Appalachia Ohio story Dark Water opens. It matters not whether we believe in God or the Devil, but the Reverend Hanson certainly does and because of that belief his behaviour subsequently becomes theatrical.

Another way to understand this is to imagine the typical conclusion of a vampire tale. A person or persons go out at midnight to dig up a grave, open a coffin and drive a stake through the heart of a corpse. This is not normal behaviour. It is exaggerated, amplified, theatrical.

We find ourselves half way through our six pillared sojourn. We have the grotesque, the ominous and the theatrical. The next pillar will connect to the previous and form our first arch. The theatricality of a gothic story is supported by its haunting quality, and all Gothic stories haunt, irrespective of whether or not they contain ghosts.

This is where, in the live lecture, I chose to read the opening of my Modern Gothic story, Livid. The reader can make their own mind up as to whether or not there are ghosts in this story, but that luxury is not granted to Alban, the protagonist. He is a haunted man. The haunting contains grotesque images and is interminably ominous. His behaviour becomes theatrical, as does that of those around him, in a literal as well as symbolic sense. The relentless pressure deepens and thins but never completely goes away. This is typical of Gothic. Think of the birds in Hitchcock’s movie. Even when they are not in shot, we know they are there. And they are there, Until the very end. And beyond. I’ve just brought them back by using the title.

Another example of this is Rebecca in Daphne du Maurier’s story who is never there but has a presence on every page. She’s even in the title which precedes all action and persists visibly when all the action has stopped. This quality is mirrored by Lauren Archer’s marvellous and truly modern Gothic tale: The Rot.

The rot in this story pervades everything, and I do mean everything. Even the deepest layers of meaning in this take on the haunted house story are infected, and that is the exquisite nature of Lauren’s tale. I am in awe of how she gets the very meaning itself to regenerate. Just like mycelium. In the lecture I read an edited extract from pages 111 and 112, but you could choose any page. Whether or not the rot is mentioned, we know it is there.

Hitchcock’s birds are not his at all, of course, he stole them from du Maurier. Her short story is much more Gothic and her birds are even more incessant.

Just one pillar left.

At this point in the lecture, I got a tad emotional. I have a visceral reaction to Lerah Mae Barcenilla’s story The City Where One Finds the Lost. I find it overwhelmingly beautiful. It also has the remarkable, and by Lerah’s own admission, entirely accidental, quality of almost perfectly reflecting instances depicted in the earlier stories whilst transporting them to a completely new environment. We had no knowledge of each other’s submissions until we saw the proof editions.

If you read the first three sentences of the story, that begins on page 131, you will hear echoes of first mine, then Michael’s and then Lauren’s stories. Then, there is sentence number four which ends:

…I realise I am dreaming.

The first line of Livid is: Have you ever had one of those dreams in which you know you are dreaming…?

I nearly choked on my breakfast toast when I first read the resurrection of that idea so early in Lerah's tale. This is probably just pure coincidence, but maybe, just maybe, it is a manifestation of the constricted nature of our genre. Our stories are wide in scope, but formed from the same few stalks. We are forced like figures trapped in secret passages to encounter the same corners, doors and iron gates. Back to the pillars.

If you read the first page of Lerah’s story (page 131) stop after the third line from the foot of the page, and savour it. There you get the first major chill of this tale. There have been lesser ones higher up the page. That is the essential use of this pillar. The chilling must not be incessant. If it were continuous, it would not be chilling, it would be frozen. As authors, we have to let it go, then we can bring it back, and let it go again, knowing it will almost certainly return.

Put that pillar in place and we have our Gothic invertebrate. Add a backbone and we have a ribcage for our Gothic heart.

I hear your objection. Any or all of those six ingredients may be found in other genres. You are absolutely right. Crime, for example, could easily accommodate them all, but our diagnosis hinges on the way they interlink – and on the crucial seventh symptom.

So, for example, if the chilling is sometimes generated by the grotesque, if the incessant pillar leads inexorably to the ominous, and if the theatrical and the haunting are mutually supportive, and if there is a spinal cord through which each of those legs can exchange electric signals with any of the others, and finally, if all six limbs individually and collectively support a vaulted canopy of gloomth: then we have Gothic.

How to use this guide: the ornithological method.

Louisa, from Fly on the Wall Press, asked how this analysis can best be used in the writing of Gothic fiction. I’m not sure that I gave the clearest answer, so I’ll try harder here.

Your best working methods are the ones that work best for you, so we may go about this in different ways, but I cannot be a planner. I get bored if I already know where I’m going. To preserve my motivation, I like to be on the same page as the reader, discovering the story as the daydream descends. A story is, quite simply, a transcribed daydream. (I may well discuss this in more detail on a future occasion, but I truly believe it is that simple.) Daydreams will go wherever they wish. How then, can analysis like this help?

Use it like a chapter of a birdwatching manual. Those chapters are often differentiated by terrain. At the coast you are looking for different species to those you will find in deep woodland, or high in mountains. Our terrain is Gothic. We are looking for our essential ingredients. If you spot something that seems ominous – focus on it. Keep it in sight. Follow it to see where it leads. If something grotesque appears – treasure it, for it is exactly the kind of component you want.

I can give you a crucial example from Livid. On the second page of the story (p28) you will find the line of dialogue:

“You will not feel my teeth on your clavicle.”

I have absolutely no idea where that line came from. It startled me when it popped into my head. It seemed so out of place, so random. Why clavicle? Why not neck, shoulder, ribcage, cheek, ear or anywhere else? And why would he not feel it? The notion was odd to the point of it being grotesque. That meant it might be invaluable. And so it turned out. It was many hours and several thousands of words before I discovered the true importance of that random idea. The whole story depended on it.

By identifying the essential seven ingredients of Gothic (the six pillars plus gloomth) we can know which ideas are likely to be the most useful in the construction of a fiction in this particular style.

I closed the lecture with the surreal tram journey that starts in the middle of page 62. In that section you should be able to find examples of the grotesque, the ominous, the theatrical, the haunting, the chilling and Alban’s own particular and incessant gloomth which, in his case, is always encased in a narrow section of the visible spectrum:

The shafts, beams, arcs and shadows are always blue. It is my constant environment. It deepens and thins, but is always there. It could be a cathedral. It is a cave. A cave without end. Labyrinthine, spherical, intestinal, interminable.

I was informed later, that during my infernal babbling of that paragraph, the door beyond the carved oak pillars behind me opened and a person emerged. Their hair was tinted blue.

I cannot thank that person enough.

For more thoughts on the six stories, see my previous post: Modern Gothic revealed

For more on the Gothic genre see the monthly posts in the Grasping the Gothic series starting with Sharpening the curve.

A Strawbs Gothic Rock playlist.

The Strawbs’ music has varyingly been described as folk, folk-rock, and progressive rock – perhaps now even geriatric rock. I would say a good sample crop of the Gothic tracks is listed below. Any fruit-based search engine will find them. I’ve given a direct link to the most Gothic example.

(All tracks written by Dave Cousins unless otherwise credited.)

- Ghosts (Lyrics used to open the lecture above. Listen here: Strawbs Ghosts)

- The Antiques Suite.

- Deadly Nightshade. (Inspired by Gormenghast.)

- Lady Fuschia (Hudson / Ford) (Inspired by Gormenghast.)

- Down by the Sea

- Burning for Me

- New World

- The Life Auction

- Midnight Sun (Cronk/Cousins)

- Lay a Little Light on Me

(Incidentally, I cannot now listen to No. 3 (Deadly Nightshade) without joyfully being reminded of the uniquely Gothic novel by Modern Gothic contributor Rose Biggin: The Belladonna Invitation.)

For more information on the Strawbs including all the lyrics of the above visit: STRAWBS OFFICIAL WEBSITE

Or for a personal introduction see my patch of posts beginning with: Savouring Strawbs

One thought on “Gloomth and the Six Pillars of (Modern) Gothic”