The swifts have gone again and once more I fear they might not come back. I am a fan of the sky-high screecher, the constantly touring devil-bird, that is shaped like a scythe, and is the fastest bird alive in level flight. Feeding, sleeping and even copulating on the wing, the focus of my fanaticism is the aerobatic marvel apus apus: the common swift.

Why am I a devotee of this hard to see, never-coming-near-me, aerial maestro? They sweep and swoop across the roof of the unspoken garden for three months every year with such grace and apparently effortless perpetual stamina. They pattern my sky. They are the ever-moving cursors sliding so elegantly between me and the clouds, or better still, between my hammock and the blue which is neither wild nor yonder, but without colour and forever. They are the animated arrows between me and infinity.

In recent years I have worried. There used to be loads of swifts sweeping high over the unspoken garden. Last year I only ever saw three at a time overhead. This year they were missing altogether. Times are hard for insect eaters. Swifts live entirely on airborne invertebrates. They take mostly the winged varieties but will also pick up others who either intentionally or inadvertently ride the wind and thermal air currents.

Invertebrates are in severe decline due to the changes in land use and the prevalence of pesticides. Drivers of my vintage will recall returning from rural excursions to find the front of the car peppered with the midges, mites, and moths that we had unintentionally slaughtered on our sojourn. These days there is virtually nothing there. Good news for insects? No. It means they are scarce. In wetter, cooler springs and summers there are fewer still, and this spring and summer has been wetter and cooler than most in the environs of the unspoken garden. I scoured the sky in search of hungry swifts and saw none.

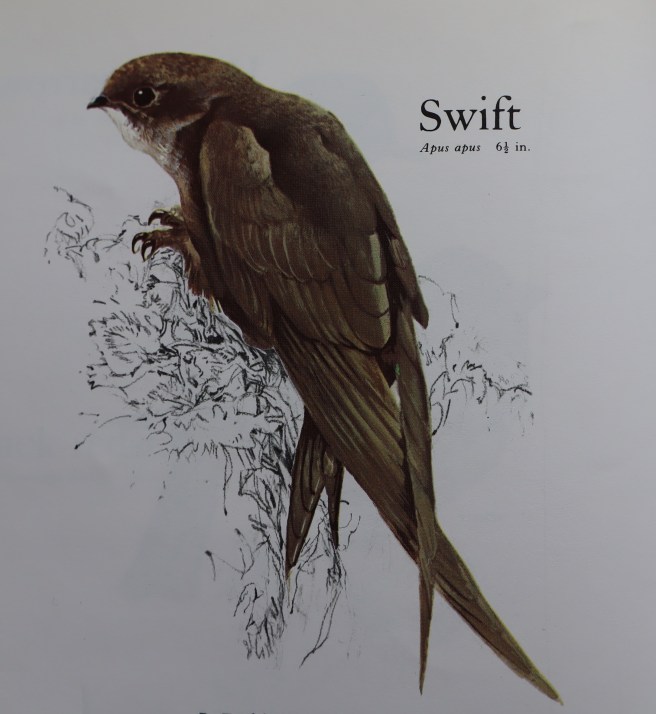

Let me clarify what I was trying to see.

The most distinctive feature of the swift is the beautiful arc of the wing profile. They have a forked tail but this is not as easy to discern and can lead to confusion with the swallow and house and sand martins. Swallows are more colourful, with significant areas of white and blue. Swifts are almost completely black-brown except for a paler patch under the chin. The house and sand martins are stubbier than both swallow and swift with the house variety sporting white rumps.

You may catch a good view of a swallow on a telephone wire, and can often see them and martins swooping in and out of their nests under house eaves or in sandbanks near rivers. Swifts also like to nest high up on buildings but modern construction techniques are denying them the plentiful opportunities to get on the property ladders that generations of their forbears enjoyed.

It is hard to believe, but scientist have proved that swifts can remain on the wing for months or even years. They only land in order to nest and feed their young. A swift on the ground is in trouble. Their wings are long and their legs are short. You can try holding it high in your open hand, but do not throw it into the air. If it is injured you may make it worse. A young swift’s first flight is actually a death-defying dive. That’s why they like to nest so high. The drop needs to be sufficient for them to pick up enough speed to generate lift. They might never touch down again for months.

Swifts migrate to east Africa for our winter. Perhaps it is more accurate to say they migrate to the UK for our summer. Our Anglo-centric pondering used to make us as why they went all that way, but a global perspective surely makes us ask why they come all this way to a cooler and much less insect-rich climate. The round trip, avoiding the Sahara, is some 14000 miles. We can imagine their disappointment, if birds experience such a sentiment, when they find bricked up nesting sites and hardly any food supplies. A parent bird will collect between three hundred and a thousand airborne invertebrates every hour while feeding its young. They will catch and pass on some twenty thousand insects and spiders per day.

Last year we saw them in May but this year there was no sign as we shivered into the wet and cold June days. I shivered even more when I thought of the missing swifts. Sarah Gibson’s informative book Swifts and Us (ISBN:9780008350666) advised me that I shouldn’t worry too much as they will fly miles to find food, but worry I did. The whole UK was experiencing a depressing ‘summer’ making me wonder just how far they’d have to fly, and whether or not they’d find sufficient flies when they’d flown there.

I kept looking and looking and no sign of swifts, and then... on 11th June we saw one. Then the secret gardener saw four. Much more recently, in July, we saw TEN. Joy of joys. They’ll be leaving soon. In fact, I think they have already gone. The squadron of ten may have been a pre-sortie mustering. They’ll be back next year, I hope.

In other birding news, one of my nest boxes – which are usually completely ignored by the local lovebirds – actually accommodated a pair great tits. The unspoken gardener heard the chicks' calls from the box which was well hidden in the laurel that terminates the badminton quad. The trail camera captured the return from shopping trips. Unfortunately, the fledging, if successful, coincided with our holiday. All was quiet when we returned, but the comfy nest was there.

Hedgehog action has continued. We are visited most nights, sometimes by two or more hogs. A fox has become a regular too. We think this may be a juvenile, and is certainly not one of last year’s visitor’s who only had half a tail. Monique the mouse (see previous unspoken posts) has vanished. The gestapo cats had been hunting her. We don’t know if they caught her, but only hogs are entering our feeding station at the moment. Talking of which, we will be providing information to the University of Reading to help with their Hogs on Film project which is a research study into the feeding behaviour of hedgehogs in gardens. If you feed and film hogs you can supply the study with data. Find them on Facebook.

From fact to fiction

Helping the unspoken gardener to foster hedgehogs provided inspiration for my latest publication.

Great Hedgepectations

People say that the old woman who lives in the house behind the high hedge always wears her wedding dress and lives in complete darkness. This does not bother the hedgehogs who sometimes stay there.

Rip, a young hedgehog who is close to death in a graveyard, has no expectations, but the two girls who find him hope to change that. What they don’t realise is that he could change their expectations too.

This adventure, inspired by Charles Dickens’ novel Great Expectations tells the story of how two girls set about helping the old woman and the hedgehogs with whom she shares her perpetual night. Rip, the orphaned hog, while negotiating the trials of a hog’s life leads the girls into danger, but also into a greater understanding of what the future might contain.

This story is suitable for adults and for older children. It contains references to historic attitudes to birth and marriage, and some scenes of animal conflict. It raises questions that might lead to useful discussions about the nature of life for animals, and for humans.

It also contains advice on how to help hedgehogs.

Proceeds from this book, including author royalties, will be donated to wildlife charities.

You can buy it here: Great Hedgepectations paperback

In the first instance, I will be donating all proceeds to Leyland Hedgehog Rescue who eased us into the process of fostering and provided the hogs that inspired the characters not stolen from classic literature. I will donate all the royalties that I receive from online sales. Should you purchase a copy from my market stall when I am on the road, the full purchase price will be donated.

As a child and young adult living in Zimbabwe, I used to see the swifts during our summer – the British winter of course – careening around the palm trees in Julius Nyerere Way in Harare.

LikeLike

What joy, Wendy. It’s amazing to think the birds you saw and those over the unspoken garden may have been the same individuals.

Sent from AOL on Android

LikeLike