Grasping the Gothic Part four: the undead

Ahead of the publication of Modern Gothic an eerie anthology from Fly on the Wall Press uneasywords is exploring the Gothic genre, its origins, influences and development.

The creche on the coast

If Strawberry Hill was the cradle of the Gothic genre, then Whitby is its kindergarten. Horace Walpole penned the first Gothic novel on the banks of the Thames west of London (see The Godfather of Gloomth) and many others followed his lead before the Irish author Abraham Stoker took a holiday on the east coast of England and dreamed up Gothic’s most renowned exponent. That’s where Stoker was inspired to commit to paper what would become the most widely known, copied, embellished, extended and spliced character of the genre.

A host of authors had cloaked their creations with varying shades of ‘gloomth’ before Stoker unearthed his depiction of an undead bloodsucker, but none of their fictional children have had the same impact, been impersonated anywhere near as many times, or – ironically for an undead individual – lived so vibrantly, so colourfully, and so frequently, for so long. Dracula is the most iconic of all Gothic characters. Irrespective of the origins of the folklore that might have spawned his creation, Stoker imported him both literally and conceptually at Whitby.

Pale and interesting

Stoker was not the first novelist to put a vampire at the beating heart of a novel. Carmilla, an 1872 Gothic novella by Irish author Sheridan Le Fanu appeared a quarter of a century sooner. It is thought that Stoker may have been influenced by Carmilla, but it is Dracula whose name is mostly found on the lips of fans of fictional blood-lovers. Stoker’s story is longer and more developed, but in common with Le Fanu, and very much at odds with later adaptations of his work, Stoker keeps the gory detail mostly at arm’s length. In keeping with Victorian expectations (Dracula was first published in 1897) the anticipation and disgust are aroused by suggestion, question and evasion. For the most part the eponymous predator is kept in the shadows. That’s where he is the most frightening.

When he does appear, however, he is simultaneously conventional and blatantly different. He seems both human and inhuman. He is glimpsed scaling the castle walls ‘lizard fashion’. He has an ‘aquiline’ face with a thin nose and ‘peculiarly arched nostrils’. His brow is ‘lofty’ his teeth are ‘peculiarly sharp’ and protrude over his lips. The general impression of his appearance is one of ‘extraordinary pallor’. It is this amalgam of the normal and the almost abnormal that is the secret of his appeal. A sense of difference is the universal condition of the human individual. We often imagine ourselves as a little more different than everyone else, while in truth, we are mostly the same. Some of those most adamant with respect to their difference can find fellowship with Dracula. Stoker’s offering is virtually religious in its value. The icon he created is statuesque.

Off the shelf

There are popular theories as to the inspiration for Stoker’s immortal character but they are not confirmed by his notebooks. It seems he discovered the word Dracula in Whitby Library, and thought, erroneously, that it was Romanian for devil. If this is true, then Dracula did indeed emerge from that coastal resort.

Stoker’s day job was that of the Business Manager of London’s Lyceum Theatre. He was in embroiled in the process of creating live entertainment which thrived on the unusual, the spectacular and the mysterious. Despite being compiled of extracts from various fictional literary sources – diaries, journals, newspaper cuttings, and a ship’s log – his infamous novel, in common with all Gothic fiction, has a distinctly theatrical quality. Dracula has a presence, onstage or off. This, above all else, may explain his endless encores.

Demeter and the dog

In the story Dracula takes a ship named Demeter and conveys boxes of earth to Whitby. By the time the boat arrives the crew are missing and there is no sign of Dracula. A dog is seen leaping ashore. The dog vanishes and the soil is transported to London by means of The Great Northern Railway. Dracula did not stay in Whitby long, but he and his kind are still there. On an overcast day in east Yorkshire there can be as many goths as gulls in Whitby.

Unfallen arches.

Whitby today, as during Stoker’s stay, is dominated by the ruins of the abbey. Yes, Gothic architecture in inspiration and in fiction, strikes again. There they are: those petrified canines. Pointed arches puncture the heavens.

Whitby is rich in purveyors of the darkest of gemstones: jet. This stone is actually fossilised driftwood from the Jurassic period and was on sale in Whitby at least thirty years before Stoker took the sea air there. It is the thoroughbred black beauty of the jewellery trade and the perfect adornment for those desiring to set off a pale complexion.

On the kind of day that Dracula would find detestable, day trippers will find Whitby delightful, but when the weather is overcast the Yorkshire cost can generate a unique atmosphere and Whitby’s protective harbour seems to gather it close. With the ruin above and the jet below it’s not hard to imagine oneself in a Transylvanian sandwich.

It was in Transylvania (Romania), sometime homeland of the Goths, that the unfortunate travellers of the novel have their most distressing encounters. The labyrinthine castle is the ideal style and in the optimum environment for the undesired mood. And so, the ingredients of Gothic are thrown together again; the background architecture, the gloomth, the grotesque, the ominous and the theatrical.

Like his subject, Stoker didn’t remain in Yorkshire long, he had a theatre to run, and a novel to write. Seven years passed following Stoker’s holiday in Whitby before Dracula made his appearance. He has never gone away.

It is interesting to me how ideas insert themselves into our heads and linger dormant, before pupating and emerging in a new form.

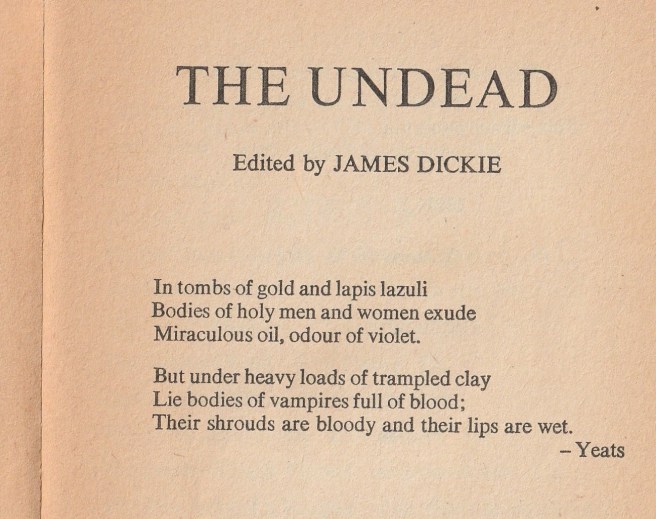

I am not deeply enamoured by vampires and my contribution to Modern Gothic is devoid of them, but there may be undead things in it. Furthermore, it is a direct descendant of a play entitled Undead, that I wrote three decades ago. The title of that drama was probably implanted in my brain by a Pan paperback anthology that lurked in my teenage bedroom, and which I still possess. I recently flicked through it for the first time in over thirty years and gasped when I read the opening line of a poem printed on the title page.

I will not, at this time, explain the reason for my shock. It will be evident when Modern Gothic is unveiled in the autumn.

Modern Gothic contains a host of characters with whom to share candlelight. Keep a copy by your bedside. It will help you sleep. Maybe.

See and hear more here: Meet the Modern Gothic Authors!

Available October 2024. Click on the cover for details and to pre-order.