Chapter seven

His father was away. His step-mother had spent an hour at her dressing table and then gone out. She did not come home that night.

The next day Nudge was back at college. She didn’t speak to Nathaniel and made no secret of actively avoiding him, so actively that she went out of her way to make sure he saw that she was avoiding him – actively.

They did not share subjects but he made sure he could intercept her. He knew what she did – Art, Biology and Geography – and the timetable was such that she had free lessons when he did not, so he was able to be outside her classroom door when Art ended. When she emerged, she looked him in the eye, immersed herself amid a gaggle of three friends, and giggled with them all the way to the girls’ toilet. He waited for her to come out. The goose trio did, but she didn’t. The bell went and he had to urgently perambulate to his English class.

He liked Gaston Ramsbottom with his Frankie Howerd face and Barbara Windsor chuckle, enjoyed the hormone-generated undulations of his fellow adolescent fledglings of the literature group, and he didn’t dislike Cymbeline with the unfortunate and, to his mind, deeply desirable Imogen, but today the coeducational amalgamation of academic insinuation, peer-pressure innuendo and uncomfortable acquiescence failed to take his thoughts off his own failings.

He was undeniably jealous of his childhood companion, Nudge, who had out-paced him to the port of lost innocence; he was perturbed by his step-mother’s unbridled hunt for hedonism, ashamed of his attraction to it, and frustrated by his inability to create and harbour something sufficiently shameful to be locked in the secret safe he had been given by telescopic Titus. But that morning, as Nudge refused to prod her way out of his contentment and he was plagued by the memory of his step-mother powdering her flower-head face above the parapet of his absent father’s garden, and as Iachimo emerged from the trunk in their studied text and crept towards the private parts of the sleeping Imogen, he fermented a plan.

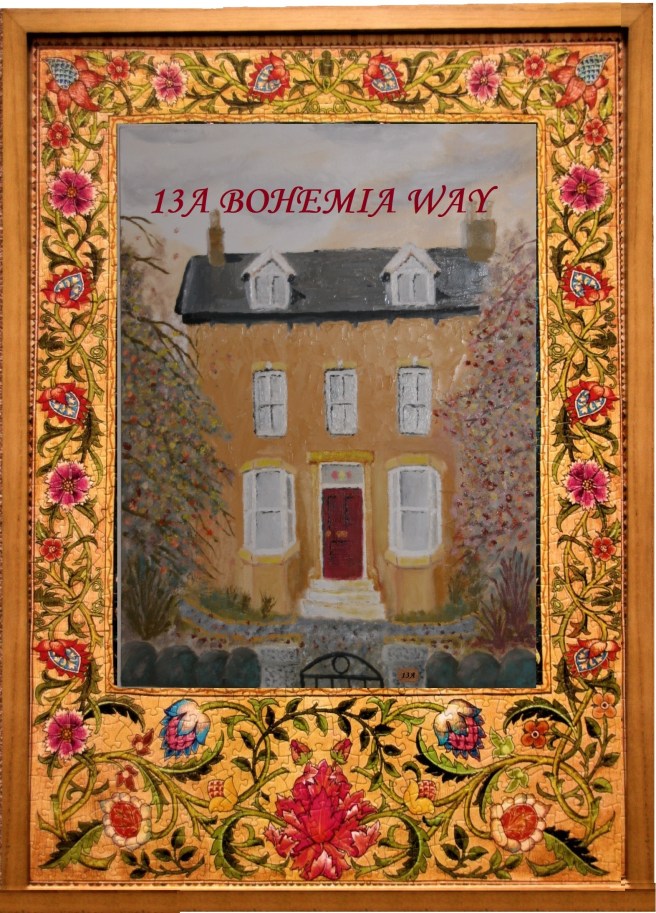

He played Nudge at her own game and actively avoided her, doing his best - though failing – to make her see his deliberate evasion, then went home to the house from which his father was working away and his step-mother was playing away, stole into their bedroom and savoured sliding open her drawer and removing the black make-up bag with the green and yellow birds of paradise paraded on it. Inside, as she had told him, was the key to her Telescopic Titus treasure box. He palmed it, took it to his bedroom, locked it inside his own box, and then took that back to 13A Bohemia Way.

The door was unlocked, as usual. The unshaven, tooth-gapped Caribbean man, whose name he still did not know, was smoking in the living room, staring at the naked electric light bulb which might have been switched on, but was not glowing due to the fact that the element had burned out some years ago.

“Hey man, thanks for wheeling me homeward,” said Nathaniel, trying his utmost to sound inclusive and cool. The reefer-inhaler smiled a grin of gratitude that was devoid of all recognition or recollection. No one else was there. No hippie in a kaftan, no happy strangers whose faces he could not reform and who numbered more than three but less than seven, no Nudge who had become a woman before he had become a man, no Deborah the pre-Raphaelite reincarnation who slept in the bath and drowned in his hopes. He hammered up the uncarpeted stairs. The percussion was plaintive.

Titus rattled the box that Nathaniel handed him. The single clink that had sounded as the parcel was passed was enough to alert his suspicions. His expression of suppressed inquisition suggested to Nathaniel that the old man had guessed at the content. He didn’t ask. Even if he had, Nathaniel would have refused to tell. Even if Titus had told him that to lock the key for one of his boxes inside another was against the rules, he still would not have admitted it. Nathaniel would have lied. He was going to lie much more frequently and much, much more fervently from now on. He had settled on that. He was going to lie joyfully, literally and biblically.

Titus unlocked his bureaux, put Nathaniel’s casket among the others and then randomly shuffled the arrangement of half a dozen boxes, as if that would further befuddle his memory of which belonged to whom.

Nathaniel was about to ask Titus if he could look through his telescope, but remembered that he was no longer polite and so simply strode bullishly to the tripod, grabbed the nipple end of the tube and put his eye to it. He was presented with an impenetrable mush. He twisted the eyepiece as he’d be taught in Physics, but although the focus sharpened, the image simply switched from soft to hard confusion. He aimed in a different direction towards the rambling rose on Mrs Emerson’s porch. He saw only jam smudges, rubber snakes and nylon ladders.

“It’s not a telescope,” announced Titus, wearily.

“That’s what my step-mum said.”

“And who might your step-mother be?”

Nathaniel’s voice box was about to put noise to her name, when he gagged it. Naming her might be a clue as to what he had put in his newly-locked box. “If it’s not a telescope, what is it?”

“A shredder-scope.”

“A what?”

“A shredder-scope.”

“What’s one of them?”

“That is,” said Titus. He came to stand next to Nathaniel. “It is my own invention.”

Nathaniel took his eye from the eyepiece and stared at the scope maker, who seemed slightly out of focus, despite the boy’s now uninhibited view. “What does it show you?”

Titus wriggled his mouth muscles and Nathaniel realised the octogenarian was not out of focus but simply old. “It shows you,” he said, “whatever you want to see.”

“Crazy.” That could have been admiration or accusation. It was both.

Titus elbowed Nathaniel out of the way, repositioned the brass tube, levelled it and peered through it. He twiddled the eyepiece, then stepped away. “Have you used a kaleidoscope?”

“Sure.”

“This is not a kaleidoscope.”

“Didn’t think it was.”

“But it has similar components. It also retains the lenses of the original telescope. Now look through. Do not adjust it. Tell me what you see.”

Nathaniel looked. “I can’t see anything.”

“Try opening your eye.”

“It is open.”

“Your mind’s eye.”

“All I can see is a mashed-up confusion of pink, yellow and brown shards. Something without any shape, any form or any purpose.”

“Excellent,” said Titus.

“What do you mean – excellent?”

Titus nodded in the direction that the shaft was pointing. “You were looking into the attic room of number nine across the road. Into the mirror on the wall. What you saw is yourself. Your description was acutely precise.”

Nathaniel walked home thinking about what he had viewed through the shredder-scope. He passed Nudge walking the other way. They both noticed how they ignored each other.

When he got home, his step-mother was at the kitchen table with a mug and a fag and a hangover. “Hello love,” she said, without unsticking her stare from the Formica.

“Good night?” he inquired.

“Too many martinis.”

“I took your key,” he said.

“Did you, love?”

“The one for your Bohemia box.”

“Bohemia box? Is that what they are?”

“I locked it in mine and threw away the key.” The last part was a lie.

“Really?”

“So, your secret is my secret.”

“How nice.”

“I looked through the scope.”

She sucked her cigarette and pinched her nose where it met her brow. “What did you see?”

“Smashed up me.”

“Join the club.”

“Is that what you saw?”

“You’ve got a visitor.”

“Where?”

“In your bedroom.”

Nathaniel’s heart was a gazelle. “Deborah?”

“Jesus.”

“Take some tablets.”

“That’s who he said he was.”

To be continued